By Haiyu Yuan

Abstract

In diesem Artikel soll ein kontingenzbasierter Ansatz in der surrealistischen Malerei untersucht werden. Dieser auf Kontingenz basierende Ansatz der Bildorganisation ist nicht festgelegt, sondern hat sich im Laufe der Zeit, vom Beginn des 20. Jahrhunderts bis heute, in der Praxis verschiedener Künstler entwickelt. Der Artikel zeichnet die auf Kontingenz basierenden Methoden der Bildorganisation und -aneignung entlang der Zeitachse der surrealistischen Entwicklung nach. Es wird auch untersucht, warum einige zeitgenössische figurative Gemälde, obwohl sie nicht mehr als surrealistisch klassifiziert werden, die auf Kontingenz basierenden Organisationsmethoden des Surrealismus weitgehend übernommen haben. Mit der Entwicklung der modernen Kunstgeschichte beschreibt der Aufsatz vor allem eine dem Surrealismus inhärente visuelle Verschiebung, die sich besonders deutlich im Übergang von der früh-surrealistischen Methode des „Automatismus“ zur pop-surrealistischen Malweise der „Bricolage“ zeigt. Diese visuelle Entwicklung hat sich ganz natürlich in die Methoden der Bildgestaltung zeitgenössischer Künstler integriert, indem sie den Zufall in die Systeme der Aneignung von Bildern auf dem Bildschirm einbezieht.

Heutzutage ist die Definition des Surrealismus extrem weit gefasst; es scheint, dass jedes Bild, das die konventionelle Realität als visuellen Anker transzendiert, als surrealistisch betrachtet werden kann. Wenn wir jedoch versuchen, dieser künstlerischen Bewegung auf den Grund zu gehen, stellen wir fest, dass der Surrealismus viel komplexer ist. In gewisser Weise ist die surrealistische Bewegung eine rebellische Ideologie, die ihre Wurzeln im Dadaismus hat und sich auf verschiedene Bereiche wie Literatur, Musik und Theater auswirkt. Der Artikel konzentriert sich jedoch auf die surrealistische Bildsprache in der Malerei, die nur einen kleinen Teil der umfassenderen Bewegung ausmacht. Das Element der Kontingenz im Surrealismus entspringt zum Teil einem rebellischen Geist, insbesondere als Widerstand gegen die großen Erzählungen des sozialen Kapitalismus. In der Malerei manifestiert sich dieses Phänomen häufig in der Dekonstruktion, Rekonstruktion und Aneignung von Referenzbildern. Die folgende Diskussion untersucht chronologisch die Entwicklung von Kontingenztechniken in der surrealistischen Malerei. Sie versucht auch zu untersuchen, wie diese Kontingenz, angewandt auf malerische Praktiken, mit verschiedenen technologischen Medien, Materialien und Räumen interagiert, um eine chemische Reaktion zu erzeugen. Darüber hinaus präsentiert die Studie zahlreiche Fallstudien von Künstlern als Grundlage für neue Einsichten und Erkenntnisse.

This paper seeks to explore a contingency-based approach in Surrealist painting. This approach to organizing images based on contingency is not static, but has evolved over time, from the early 20th century to the present, in the practices of various artists. This article traces the methods of organizing and appropriating images based on contingency along the timeline of Surrealist development. It also examines why some contemporary figurative paintings, while no longer categorized as Surrealist, has largely adopted Surrealism’s contingency-based methods of organization. With the development of modern art history, this essay primarily describes a visual shift inherent to Surrealism, which is particularly evident in the transition from the early Surrealist method of „automatism“ to the Pop Surrealist painting method of „bricolage“. This visual progression has been naturally integrated into the image-making methods of contemporary artists, incorporating chance into the systems of appropriation of the screen image.

Nowadays, the definition of Surrealism is extremely broad; it seems that any image that transcends conventional reality as a visual anchor can be considered surrealistic. However, when we try to trace this artistic movement, we find that Surrealism is much more complex. In some ways, the Surrealist movement is a rebellious ideology rooted in Dadaism that has influenced various fields such as literature, music, and theater. However, the focus of this article is on Surrealist imagery in painting, which is only a small part of the broader movement. The element of contingency in Surrealism arises in part from a rebellious spirit, particularly as a form of resistance to the grand narratives of social capitalism. In painting, this phenomenon often manifests itself in artists deconstructing, reconstructing, and appropriating reference images. The following discussion chronologically examines the development of contingency methods in Surrealist painting. It also attempts to explore how this contingency, applied to painting practices, interacts with various technological media, materials, and spaces to create a chemical reaction. Furthermore, this research presents numerous case studies of artists as a basis for new insights and knowledge.

1. Surrealism and Automatism

In 1917, the litterateur André Breton, while working as a psychiatric assistant in a military hospital, witnessed the rise of the anti-traditional Dada movement in Zurich. At the inception of the concept of Surrealism, Breton took Freud’s psychoanalysis as a practical reference and probed further into it, extensively incorporating the understanding of the subconscious and dreams into the construction of symbols between subject and consciousness. In the process of using psychoanalysis as a reference, a noteworthy concept derived from Surrealism is “Automatism.” Breton mentioned it in his writings, “I resolved to obtain from myself what we were trying to obtain from [patients], namely, a monologue spoken as rapidly as possible, without any intervention on the part of the critical faculties…” (Breton 1924). This concept was initially applied to contingent creative writing, capturing the innermost noise by recording key words and images through a stream of consciousness. It was one of the core methodologies of early Surrealism, allowing imagination and contingency of consciousness to take over all expressions of creativity. It’s challenging to concretely measure how much “Automatism” influenced artists in weaving illusions on their canvases, as French artist Max Morise pointed out in his 1924 article Les Yeux enchantes that there was no universally accepted or clear definition of Surrealism, let alone Surrealist art (Morise 1925). Although the logic of Surrealist creation is often criticized as ambiguous, it is this cross-media approach that ties poetry, painting, sculpture, and other forms to Surrealism. Surrealist artists, through random streams of consciousness, demonstrated the shared characteristics of the movement across various artistic forms. The imperfect, incomplete, fluid, and unstable spatiotemporal states are evident in the poetry and prose created by early Surrealists. Surrealism seems to have been designed from the outset to accommodate diverse cultural and visual systems, allowing individuals to freely explore their imagination on its blueprint.

The development of Surrealist painting is well-known for its contradictions and controversies. Andre Breton had a very one-sided perception of painting as a medium of expression. In his essay Le Surrealisme et la Peinture, he focused more on the superficial imagery conveyed in the paintings rather than the techniques and media, describing a painting’s visual composition merely as a window to view landscapes (Breton 1965). Salvador Dalí joined the Surrealist movement in the early 1930s, identifying as a mainstream representative of the movement. However, in 1934, he was expelled from the movement by Breton and other Surrealist leaders due to political and commercial disagreements. This did not prevent Dalí from laying the groundwork for Surrealist art, especially through his painting methods. In 1932, Lacan in his doctoral thesis articulated a concept of “paranoia” and creatively linked it with Dalí’s artistic creation. Lacan suggested that paranoid patients often cannot properly distinguish between self and the external world, which may manifest as an over-perception or illusion of external threats (Lacan 1932). In Dalí’s works, the faculty of paranoiac expressed an almost paranoid identification of visual symbols, continuously positioning contingent imagery combinations originating from the subconscious. The way visual symbols are selected and applied to the overall atmosphere of a painting reflects how subjects and symbolic meanings are bound in a framework of cognition and choice.

What is most noteworthy is that in Dalí’s contingent positioning process, image appropriation indeed occurred, and its organization did not culminate in a representation of reality but in the “dream world” claimed by Surrealists. From a methodological perspective, this can be understood as an upgraded version of “Automatism,” which aided early Surrealist artists in locating and visualizing the spectral images emerging from the depths of their consciousness. In an interview, Dalí revealed that these images came from the visions he experienced in the 10 to 15 minutes before falling asleep. He believed that during this time, rationality occupied only a small part of his imagination, and the images captured at this moment were devoid of meaning or interpretation but full of mysterious allure. These early Surrealists advocate extracting instantaneous images from the depths of personal consciousness, describable as “randomness” but more accurately as “improvisation”. This “improvisation” in their methodology is inward-out, whereas contemporary Artists often urgently need an external visual system related to interfaces or online experiences in their image composition. On the other hand, the interpretation of Surrealist painting often greatly involves imagery space and symbolism, meaning that the narrative path of the painting is not directly anti-storytelling but rather emphasizes interpretation and metaphor. Breton and Dalí, despite ideological opposition, both believed that through the awakening of the unconscious, people could achieve true liberation. Surrealist scholar Gloria Duran in her 1988 article stated, “Most surrealists, however, ignored Freud’s negative approach to the unconscious, and used Freud as a scientific justification for rebellion against family, society, and morality in general.” (Duran 1988) This suggests that the unanimous goal of Surrealists was to construct a narrative of resistance and liberation aided by the unconscious.

2. Pop Surrealism: From Automatism to Bricolage

Continuing along the thread of Surrealism, pop surrealism quickly comes into view. Some critics like Mauro Tropeano (2010) believed that Pop surrealism originated from the “Low Brow” movement and is sometimes associated with the “Bad Painting” movement, as noted in Lowbrow Art / Pop Surrealism. It aims to rebel against the traditional gallery-artwork system and the elite mainstream of the art world at that time. Influenced by the counterculture and pop art movements starting in the 1950s in America, this new aesthetic approach required a reevaluation of youth popular culture and subcultures, including comics, rock music, and Hollywood movies. The peculiar, unique, and commercially symbolic visual narratives combined Dadaism and pop art to gain a place in middle-class aesthetics, even encroaching on artists’ and the public’s vision and thinking to some extent. A flood of related creations initially dominated the illustration field, then expanded across painting, sculpture, and moving images. In this context, the incessant repetition and consumption of certain visual forms can be seen as a form of political correctness, where the standardization of imagery serves to uphold prevailing cultural norms and expectations, stifling originality and critical engagement. At first glance, it appears to be a mix of surrealism and pop art, but it is not as large-scale or widely recognized as early surrealism. It wasn’t until 1981 that artist Kenny Scharf extensively used the term in his works. The exhibition “Pop Surrealism” at the Aldrich Museum of Contemporary Art from June to August 1998 further solidified this concept. In appearance, the pop surrealism style closely resembles contemporary figurative painting, especially in the appropriation and organization of mass images and the increasingly secular aesthetic system. However, from perspective of contingency, this represents a shift from “Automatism” to “Bricolage.”

Georges Bataille criticized Surrealism for its paradoxical expectation of exposing the unconscious while reverting to recognizable illusions (Bataille 1948). Early Surrealists, employing “Automatism,” linked their techniques to seances, “spiritual writing,” and unconscious speech, striving to depict the unconscious. In his 1922 essay The Mediums Enter, André Breton defined “Surrealism” as “a sort of mental Automatism,” aiming to translate pure inner experiences into visual resonance (Breton 1922). Unlike spiritualists who believed these inner voices were external, Surrealists saw them as stemming from the unconscious mind. The intertwining of culture and commerce in the art world is not a recent development. It began much earlier, from the Renaissance through the late 19th century, and continued into the Avant-Garde and Pop Art movements. By the late 20th century, it became increasingly difficult to rely on unconsciousness—whether from the artist’s personal vision, the artworks themselves, or external cultural forces—without incorporating ready-made images from screens, magazines, and streets. The fusion of pop’s superficiality and Surrealism’s disruptive anarchy released a mixture of middle-class anxiety and excitement, morphing into a paranoid and morbid sense of humor.

In contrast, Surrealists matured in a pre-modern society influenced by natural experiences. For instance, Miró’s landscapes inspired by his childhood in rural Spain, while Max Ernst deconstructed impressions of his urban life and social circles. Postmodern pop artists, despite their rebellious spirit against capitalism and a unidimensional society, struggled to maintain the straightforward experiences of their predecessors. The allure of cartoon images, captivating typography, dazzling urban colors, and complex jazz symphonies facilitated a shift from spontaneous “Automatism” to the limited choices of “Bricolage”.

In anthropological research, the concept of “Bricolage” first described as “achieving goals or objects with whatever is at hand” or “collecting human leftovers to solve problems” (Lévi-Strauss 1966). Compared to the automatic derivation and natural state of the unconscious in “Automatism,” “Bricolage” is a more eclectic methodology. Iain Biggs views “Bricolage” as a metaxy of practice—a “space in-between” where one can operate in an “undisciplined” manner, free from institutional or disciplinary constraints, which is useful for understanding how academics or artists navigate and create in various landscapes (Biggs, 2010). Artists first address the fundamental questions of their work—what to create, express, and how to do it. Early surrealists often reflected on and integrated their experiences and dream imagery, aiming to evoke subconscious resonance in the viewer by drawing on classic colors and compositions. In contrast, pop-surrealism artists have easier access to materials, with a vast reservoir of images, information, and cultural symbols available in media, films, comics, and magazines. Everything, including implied, metaphorical, and hybrid elements, seems readily available and widely appreciated.

Kenny Scharf’s early creative experiences highlight the significant roles of contingency, serendipity, and Bricolage-style assemblage. Before formally starting his art career, Scharf consciously drew inspiration from advertisements and television imagery, using tools, materials, and discarded items around him to customize and modify everyday objects, which he sold on New York streets. This fascination with trash and keen observation of life directly influenced his installations and paintings. For example, his “Cosmic Cavern” series is a constantly evolving space, with Scharf continually adding new materials found in trash dating back to 1980 (Fig. 1). “Besides trash, it can be anything I encounter” (Scharf 2011). In Scharf’s paintings, the appropriation and transformation of pop symbols and images are specific and traceable, whereas his paintings, filled with chaotic, organically growing cartoon figures, reflect subconscious suggestions. In an interview, Scharf mentioned that these creatures originate from his imagination, representing a mutation of images connecting the past (Jetsons) and the future (Flintstones), with a touch of Felix the Cat. Similar to jazz performance, the artist organizes, deconstructs, and assembles existing inspirations while adhering to certain established rules of expression.

Figure 1: Kenny Scharf, Cosmic Cavern, installation view, Nassau County Museum of Art, Roslyn, March–July 2016 (artwork © Kenny Scharf, provided by ARTnews, 2024).

However, it is important to note that the concept of “Bricolage” is not exclusive to pop-surrealism. Artists like Robert Rauschenberg exemplify the post-avant-garde’s use of found objects from their environment. Rauschenberg’s assemblages of random order significantly impacted modern art, indicating a responsibility not only to pop art, assemblage, and collage but also to minimalism and avant-garde readymade. Lévi-Strauss stated, “The bricoleur embraces uncertainty, instability, and danger, not limiting themselves to achievements but creating new relationships through mediation between objects”. While it’s challenging to determine if pop-surrealism artists establish new relationships between mediums, it’s clear they continually integrate newly perceived images into their works, even if this assembly appears random and abstract. Existing images, styles, and motivations occupy their subconscious, awaiting organized expression.

The contingency reflected in “Bricolage” differs from that in “Automatism” in that its scope may extend across an artist’s entire career, causing their work to exhibit markedly different appearances based on the experiences at different stages of their life. Philip Guston is undoubtedly a quintessential example in this regard. Guston’s early work is generally considered the most easily categorizes and analyses by critics and curators, stemming from Guston’s refinement of the pictorial styles and structural forms of early Renaissance painters such as Paolo Uccello and Piero della Francesca. In these classical works he uncovered a refined summary of the image that transcended its time and combined it with what he called “cubist conceptions of space”. Guston’s second major phase is an expressionistic abstraction that was the opposite of his earlier figurative style, with the simplicity and haziness of Monet’s Impressionism in colour and the deliberate retention of brutality in his brushwork. This phase of Guston’s work was inspired by references to abstract artists such as his friends Jackson Pollock and John Cage, as well as by his own thoughts on Zen Buddhism. Later, around 1970, Philip Guston launched his controversial period of figurative cartoon painting in art history, which for the first time conjoined an open relationship between political identity, anarchy and ordinary objects. The Ku Klux Klan images, cigarettes, shoes, easels, planks of wood, dust bins, etc., images of mondains catalyse the ironic spectacle of carnivalesque grotesquerie with subversions, distortions and clumsiness, which reflect the assemblage from eternal human conflict to the absurd. These three distinct stages each reflect the artist’s choice of entirely different styles as a means of expression, inspired by the contingencies encountered in different experiences.

Interestingly, however, these seemingly different stages are, in fact, internally interconnected. Guston’s engagement with cartoonish lines stems partly from the abstract calligraphy of his early expressionist work—simple, unintentional, and brimming with life–which imbues these objects with a heightened sense of value. It also partly derives from his imitation of Robert Crumb’s comic imagery, which connects his work to pop culture, remnants of social structures, and fragments of reality woven into allegories (Fig. 2). Remarkably, many of these objects existed in Guston’s mind long before he formally entered the art world. They include memories from his childhood, such as witnessing his shoemaker father at work, the chandelier in his studio, the discarded items outside his home, and the haunting presence of the Ku Klux Klan. The origin and appropriation of these images suggest an inside-out space of choice, akin to ‘Bricolage,’ yet latent within the process of ‘Automatism.’ Through this process, Guston transforms the subconscious into tangible figures within his work, culminating in a biographical narrative mode deeply oriented towards the artist himself. Although Guston’s work clearly conveys a desire to narrate a story or at least a narrative, this intention is not immediately apparent when simply gazing at the images. It is only through an understanding of Guston’s background that one can uncover the intricate relationships between the images and the underlying reality they reflect. This process also underscores the significance Guston places on the materiality of his work, highlighting how the physical medium becomes a vessel for personal and historical narratives. As he once expressed:

“I feel as if I’m shaping something with my hands. I feel as if I’ve wanted always to get to that state. If a blind man in a dark room had some clay, what would he make? . . . I always thought I was a very spiritual man, not interested in paint, and now I discover myself to be very physical, and very involved with matter.” (Guston 1990)

Figure 2: Philip Guston, The Studio, 1969, oil on canvas, 71 × 73 3/10 inches (180.3 × 186.1 cm) (artwork © Philip Guston, provided by Artsy, 2024).

3. Contingent Encounter Between Surrealist Painting and Technological Media

“Bricolage,” as a method of appropriating the image space of the other, simultaneously implies the potential for communication and connection between various elements. Unlike the cases of artists Kenny Scharf and Philip Guston mentioned earlier, here we will discuss a contingency shift oriented towards technological media. Gerhard Richter and Luc Tuymans are undoubtedly key figures in this shift. Their paintings often convey a simulation of photographic and screen images, constantly reminding viewers that they are looking at a visual illusion appropriated from a technical medium. To trace why some contemporary younger artists like Gao Hang, Issy Wood, and Louise Giovanelli choose to directly appropriate screen images into their paintings and what this signifies, we might find clues in the creative logic of Gerhard Richter and Luc Tuymans.

Since the mid-19th century, when most artists used photography as an aid to painting, Gerhard Richter chose to break the conceptual and formal framework between painting and photography. This is particularly evident in his well-known “photo paintings.” These works mimic the visual aspects of photography, attempting to manually replicate the chemical reactions seen in photos. Richter anchored his visual contingency on mechanical reproduction, erasing brushstrokes and using projectors to transfer photos onto canvases for accurate replication. In a 1972 interview with Die Zeit, Richter highlighted the importance of photography in his painting process, stating, “It has no style, no composition, no judgment. It frees me from my personal experience.” (Richter 1972) This exclusion of subjective action positioned Richter as a key figure in conceptual painting, continuously exploring the boundaries between photography and painting. Photography, driven by technology and equipment, can maximize objectivity by eliminating personal expression, a feat nearly impossible in painting. Even Richter’s “photo paintings” cannot completely detach from personal experience. However, it is worth noting that, at first glance, Richter’s paintings seem closer to a distinctive photorealistic atmosphere, yet they can still be regarded as a form of Surrealist expression. In his 1964-1965 notes, Richter explicitly declared, “I am a Surrealist.” Susan Laxton, in her research on Richter, also pointed out that Richter’s practice can be understood as a repeated enactment of photographic Automatism, contingency, and the relinquishment of control over the image (Laxton 2012). This partly explains why Richter abandoned conscious decision-making in his painting practice, opting instead for methods that are driven rather than self-determined. He clearly aimed to delegate visual authority to technological media to achieve a genuine inspiration through contingency.

Benjamin’s Little History of Photography offers a plausible explanation for Richter’s approach, depicting the use of images determined by others (Benjamin 1927-1934). This allows the artist to avoid integrating themselves into the composition, using photographs as guides while the paintings reflect the photos. However, Richter’s works cannot be defined as photo-realism due to his unique treatment of blur. Using tools like scrapers, Richter creates “precise blurriness,” promoting image equality by preventing the viewer’s eyes from resting on specific objects, encouraging the search for recognizable shapes. When absent, the plan fails. Thyra Knapp interprets this blurriness in Richter’s paintings as fostering equality among images: “Richter’s objective aesthetic choices to use gray and blur the lines lend themselves particularly well to the works discussed here as they are photo paintings; the viewer has seen and expects to see photos both in shades of gray and out of focus. Furthermore, even in today’s world of digitally enhanced photography, there remains a belief that photographic images are innately objective and free of bias.” (Knapp 2012) While Peter Osborne noted, “Photo-painting acts to add a moment of cognitive reflection, of historical and representational self-consciousness, to the experience of the photographic image. It creates a space and a time for reflection upon that image which is qualitatively different from that of the photograph itself, haunted as such experience is by the trace of the object.” (Osborne 1992)

The transition from photo painting to screen painting was natural and smooth for Richter. Functionally, there was no significant difference for him between sourcing images from photos and from screen images. Take one of his most representative works, September for instance. It depicts the scene after the airplane struck the Twin Towers on September 11, 2001, derived from live television broadcasts. Richter faithfully reproduced the smoke-billowing towers and used his signature squeegee to blur the image, creating what he described as, “with the garish explosion beneath the wonderful blue sky and the flying rubble.” (Richter 2023) This surface damage on the painting corresponds to the real historical destruction depicted, drawing a rift between public memory and authentic visual documentation (Fig 3). There seems to be no technical or visual barrier in transitioning from photo to screen image appropriation. This is not because there is no difference between photos and moving images in the painter’s subjective world, but because Richter instinctively applied his photo painting experience to screen images. While this may have set a standard for medium conversion for later artists, it does not necessarily explain their motivations. Like how early Automatism evolved around 1990 due to changing cultural contexts, new generations of artists will inevitably adapt their strategies to contemporary cultural, social, and technological backgrounds.

Figure 3: Gerhard Richter, September, 2005, oil on canvas, 52 x 72 cm (artwork © Gerhard Richter, provided by the artist‘s official website, 2024).

Luc Tuymans, 25 years younger than Richter, grew up with television images and truly contextualized the contingency of moving images into painting. In a 1996 interview, Tuymans said, “For my generation, television is very important. There’s a huge amount of visual information which can never be experienced but can be seen, and its impact is enormous…. For an artist like Gerhard Richter, the fight of true painting against photography was very important; for me it’s much more interesting to think in terms of films, because on a psychological level, films are more decisive.” (Tuymans 1966) However, this does not explain why Tuymans’ paintings often feature gray, low-saturation, and barren tones. Early television images had various degrees of saturation, as contemporary artist Joseph Yaeger, who also appropriates vintage screen images, often presents vivid, high-saturation colors. Tuymans’ painting style is clearly distinct and personal, differing from Richter’s emphasis on objectivity.

In the same 1996 interview, Tuymans expressed his indifference towards photographs but showed great interest in filmmaking. He believed painting and film shared similarities, particularly in how painted images could be seen as a form of editing, suggesting content beyond the canvas’s boundaries. He aimed to evoke the passage of time through the negative space in his narrative, later referring to this as “painted time.” In a 2005 summer conversation with artist Kerry James Marshall, Tuymans discussed the contingency artists face when handling images. He mentioned that his work often explores imperfect images, viewing these imperfections to capture a different kind of perfection in the outdated medium of painting. (Tuymans 2005) In this process, he sought out the “weak points” or “voids” in images, incorporating them into his work. Consequently, Tuymans often selected the most blurred, fragile, and neutral parts of screen images as references. Through these images, he created an imitation of the illusion left by low-quality technical images on the canvas.

This differs markedly from Richter’s intentional creation of blurred illusions with a squeegee tool, as Tuymans’ approach is highly personal and subjective (Fig. 4). In interviews, these personal marks seem rooted in his suggestion of the inaccuracy of memory. Scholar Stephen Moonie argues that these paintings reflect the manufacturing nature of images under late capitalism’s sheen, exposing the artist’s skepticism towards this technical illusion. Regardless of interpretation, these concepts significantly aid in establishing the framework of “Bricolage”. The articulable elements have been adopted and developed by various contemporary artists, making similar paintings easily accepted by markets and collectors today.

Figure 4: Luc Tuymans, Eternity, 2021, oil on canvas, 55 x 43 1/4 inches (140 x 110 cm) (artwork © Luc Tuymans, provided by David Zwirner, 2022).

4. Embracing the Contingency of Screen Images:

A New Illusion in Contemporary Figurative Painting

Since Tuymans, the contingency-based organizational form of Surrealism has seamlessly integrated into the image systems of easel painting. “Bricolage” has become a subtle presence in contemporary painting practice, evident in the contingent creations of the younger generation of artists working with screen images. Unlike in Tuymans’ time, contemporary screens are digital rather than traditional television screens. One particularly relevant art critique is the article Digital Archaeology, Sketching, and Innovation in the Screen Generation Paintings, The author Wang Jiang refers to these artists as the “Screen Generation”, indicating a generation shaped by electronic screen experiences. He also describes them as a “fractured generation,” marked by significant visual shifts in their art—identifiable by spectrum-like color configurations and layered spatial effects. These images appear on screens, creating an alternative “reality” and “nature.”

Wang Jiang considers these paintings the new norm in contemporary art history, each with its unique narrative depth behind their screen expressions. He analyzes and evaluates the characteristics of 17 Chinese artists paintings. For instance, he notes that Gao Hang’s paintings feature “sharp, pixelated edges and many distorted details that visually impact the viewer, revealing the obscured realities beneath the surface” (Fig. 5). Regarding artist Du Jingze (Fig. 6), Wang Jiang observes that his “technique superficially simulates digital technology, but it conspires with elusive images to create a formal strategy. Its smooth texture allows the artist to transcend East-West differences, achieving a global citizen’s freedom.” Artists like Hou Jianan (Fig. 7) are noted for “depicting symbolic objects in social ’rituals’ with a psychoanalytic tone. Today, human interactions are alienated into performances. He translates excessive material into symbolic codes, satirizing consumerism.” Wang Jiang also mentions artists such as Rao Weiyi (Fig. 8), Xia Yu (Fig. 9), and Feng Zhijia (Fig. 10), who embrace the aesthetics of “glitches” caused by algorithmic errors, asserting that “these anomalies first undermine the subject’s self-assuredness in a singular system. Just as electronic faults often stem from human-computer interactions, the exact source of light spots in paintings arises from the artist’s interplay with the creative process, revealing the fundamental randomness, instability, and unpredictability of technical systems.”

Figure 5: Gao Hang, Auto Tune, 2020, acrylic and gel on canvas, 30.5 × 22.9 × 5.1 cm (artwork © Gao Hang, 2020).

Figure 6: Du Jingze, Fruit Garden, 2020, oil on canvas, 150 × 150 cm (artwork © Du Jingze, 2020).

Figure 7: Hou Jia-Nan, Performance, 2023, acrylic on canvas, 185 × 250 cm (artwork © Hou Jia-Nan, 2023).

Figure 8: Rao Wei Yi, Hunting, 2023, acrylic on canvas, 180 × 150 cm (artwork © Rao Wei Yi, 2023).

Figure 9: Xia Yu, The Long Song, 2022, tempera on canvas, 300 × 600 cm (artwork © Xia Yu, 2022).

Figure 10: Feng Zhijia, Window Sill, 2021, acrylic on canvas, 160 × 120 cm(artwork © Feng Zhijia, 2021).

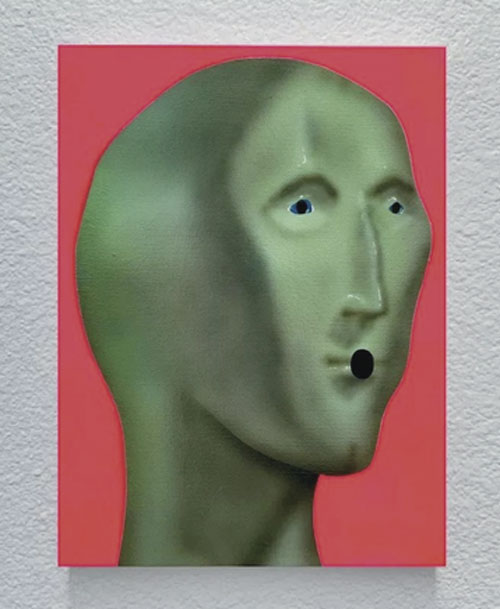

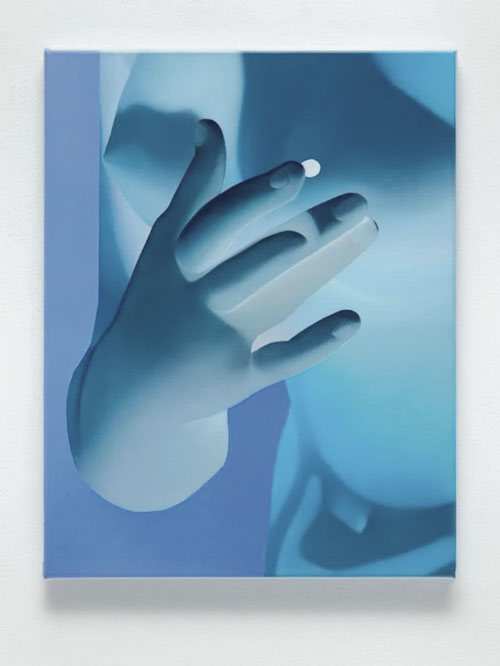

Although the above discussion of the “Screen Generation” primarily focuses on Chinese artists, this trend of painting based on digital screen images is global. For example, born in 1989 in Switzerland, Louisa Gagliardi is also a quintessential “Screen Generation” artist known for transporting and intricately editing online images in her creations (Fig. 11). Artforum’s article by Agata Pyzik provides a balanced review of Gagliardi’s work. Pyzik describes the Photoshop-like surreal and curated landscapes in her art, subtly questioning the overuse of screen media and the physical discomfort induced by such “screen-like” visual effects (Aranda 2024). However, the article concludes by acknowledging Gagliardi’s disruptive exploration of self-image in late capitalism through her painting concepts. The other Artforum articles also interpret the digitalized or screen-like visual aspects of artists’ works. For example, in an article about German artist Vivian Greven (Fig. 12), it is mentioned that:

“Apple, the title of Vivian Green’s latest exhibition, evokes a neat range of associations, from the Tree of Knowledge, to William Tells arrow, to the computer brand. If the fifteen paintings here recall ancient Greek statuary in their depictions of smoothly modeled nudes, their finely glazed shapes and electric sheen also suggest the inhabitants of digital nonspace. Existing somewhere between Adonis and avatar, the figures never fully register as flesh.” (Benschop, 2021)

Figure 11: Louisa Gagliardi, Under the Surface, exhibition view, Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zurich, 2024 (artwork © Louisa Gagliardi, provided by Artforum, 2024).

Figure 12: Vivian Greven, Qulla I, oil and acrylic on canvas, 2020 (artwork © Vivian Greven, provided by Artforum, 2020).

American artist Louise Giovanelli is perhaps one of the most sought-after members of the current “Screen Generation” (Fig. 13), an articles attempt to dissect how the artist gradually guides the viewer’s visual experience:

“The artist invests portraits with high drama, evoking an uncanny feeling of suspense. The viewer is led to imagine what might happen next, or what might have happened before, without being able to define the vaguely troubled, emotional flavor of the moment at hand. Time and again, she presents us with the same ethereal scene, one that would otherwise disappear in the fleeting temporality of a cult movie.” (Benschop 2023)

Figure 13: Louise Giovanelli, Golden Hour, exhibition view, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, May 10, 2023 – September 17, 2023 (artwork © Louise Giovanelli, provided by Artforum, 2023).

From the works of these “Screen Generation” artists, we can clearly sense their fascination with the contingent organization of digital images. This form clearly continues the Surrealist shift from Automatism to Bricolage, and coincidentally, these developments occur in the realm of easel painting rather than digital painting. These paintings suggests a two-dimensional screen space that can be infinitely artificially synthesized. It is not a technical medium but an image carrier used to simulate and organize visual productions that do not actually exist. The contingency in contemporary image organization is reflected in Flatness Juxtaposition. I believe this is a very important start point because it implies how contemporary artists perceive various image archetypes in painting. On the surface, Flatness Juxtaposition merely describes a flattened montage stitching method, similar to early forms of collage. However, the current situation is that artists tend to view image archetypes in their paintings as images themselves, based on screen media. These images are fundamentally dematerialized and not subject to real-world gravity, allowing artists to embrace the contingency of screen Images and manipulate and edit them freely in their paintings. To understand this form, one must completely abandon classical spatial perspective and instead adopt a screen-based perspective. In the screen context, there is no meaningful sequence or order; images and windows coexist simultaneously. The artist operates more like a user in front of a screen, trying to call up and display the desired images on the monitor. Since images are merely images and do not require any form of understanding or recall of their materiality, nor verification of their original context or state, artists can easily focus on the composition, color coordination, and provocative visual experiences as the ultimate standards in their painting.

In contrast to the early Surrealist shift from Automatism to Bricolage, the contingency of the “Screen Generation” seems to be confined within the interface of digital screens. If a creative action originates from technological imitation and observation, it likely concludes in the same realm. As observers of contemporary screens, artists inevitably believe they understand and master everything in painting. However, in reality, they are merely treating the world as images themselves. This situation easily traps artists within the framework of screen aesthetics. At the same time, we observe that Surrealist painting, which was originally meant to resist and deconstruct capitalist imagery, has now been reintegrated into the financial value chain. This indicates that as contingency in Bricolage methods evolves toward the limitations of eclecticism, a significant challenge remains for painting to respond to the notion that “Painting Is Dead” in the contemporary environment.

Bibliography

Alberti, Leon Battista: On Painting. Trans. John R. Spencer. New Haven, CT [Yale University Press] 1966

Aranda, Julieta: Louisa Gagliardi. In: Artforum. Galerie Eva Presenhuber, accessed June 22, 2024. Available at: https://www.artforum.com/events/louisa-gagliardi-247149/.

Ashton, Dore: A Critical Study of Philip Guston. Berkeley [University of California Press] 1990

Auping, Michael: Philip Guston: Retrospective. London [Thames & Hudson] 2006

Bataille, Georges: Inner Experience. Translated by Leslie Ann Boldt. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1988.

Bataille, Georges: The Surrealist Religion [1948]. In The Absence of Myth: Writings on Surrealism, edited and translated by Michael Richardson, 72. London: Verso, 1994.

Benjamin, Walter: “Little History of Photography.” In: Jennings, Michael W.; Howard Eiland; Gary Smith (Hrsg.): Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings, Volume 2, 1927-1934. Cambridge, MA [Belknap Press of Harvard University Press] 1999, S. 507-530

Benschop, Jurriaan: “Louise Giovanelli”. In: Artforum. May 10, 2023 – September 17, 2023. Curated by Mark Richard Smith, Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Available at: https://www.artforum.com/events/louise-giovanelli-251120/.

Benschop, Jurriaan: Vivian Greven. In: Artforum. November 21, 2020 – May 30, 2021. Available at: https://www.artforum.com/events/vivian-greven-248456/.

Breton, André: Le Surréalisme et la Peinture. Paris [Gallimard] 1965

Breton, André: The Mediums Enter. In: Breton, André (Hrsg.): Manifestoes of Surrealism. Ann Arbor [University of Michigan Press] 1972, S. 26

Cavett, Dick: Salvador Dalí On The Meaning Behind His Art, The Dick Cavett Show. August 22, 2020. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A3FAy0teMNo .

Crary, Jonathan: Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century. Cambridge, MA [MIT Press] 1990

Duran, Gloria: Surrealism and Psychoanalysis. In: Modern Language Studies 18, no. 2, 1988, S. 10-11

Epstein, Mikhail: “The Interesting”. In: qui parle 18, no. 1, 2009, S. 85.

Felsenthal, Julia: Jacqueline de Jong Paints It All. In: Houldsworth Gallery vom September 15, 2021. Available at: https://www.houldsworth.co.uk/press/153-jacqueline-de-jong-paints-it-all/.

Gronlund, Melissa: Contemporary Art and Digital Culture. New York [Routledge] 2016

Hoy, Meredith Anne: From Point to Pixel: A Genealogy of Digital Aesthetics. Lebanon, NH [Dartmouth College Press] 2017

Kahnweiler, Daniel-Henry: The Rise of Cubism. Trans. Henry Aronson. New York [Wittenborn, Schultz] 1949

Klein, Richard; Dominique Nahas (Hrsg.): Pop Surrealism. Ridgefield, CT [Aldrich Museum of Contemporary Art] 1998

Knapp, Thyra E.: Gerhard Richter and the Ambiguous Aesthetics of Morality. Colloquia Germanica 45, no. 1 (2012): 97.

Lacan, Jacques: De la psychose paranoïaque dans ses rapports avec la personnalité. Paris [Seuil] 1975

Lacan, Jacques: Écrits: A Selection. Trans. Alan Sheridan. New York [W. W. Norton & Company] 1977

Laxton, Susan: As photography: Mechanicity, contingency, and other-determination in Gerhard Richter’s overpainted snapshots. In: Critical Inquiry, 38(4), 2012, 776-795.

Lévi-Strauss, Claude: The Savage Mind. London [Weidenfeld and Nicolson] 1966

Mersa, Auda: Surrealism Beyond Borders at Tate Modern: A Reimagining of Life Through Art. In: The Independent, 2022. Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/surrealism-beyond-borders.

Morise, Max: “Les Yeux enchantes.” La Révolution surréaliste 1, no. 3 (April 1925): 14.

Osborne, Peter: “Painting Negation: Gerhard Richter’s Negatives”. In: October 62, 1992, S. 103-113

Polizzotti, Mark: Revolution of the Mind: The Life of André Breton. New York [Farrar, Straus and Giroux] 1995

Spampinato, Fabio: “Kenny Scharf: Bringing the Fantasy into Reality”. Italian Vogue, 2011, S. 193-205

Steyerl, Hito: Too Much World: Is the Internet Dead? In: Aranda, Julieta; Brian Kuan Wood; Anton Vidokle (Hrsg.): The Internet Does Not Exist. Berlin [Sternberg Press] 2012, S. 11-15

Tropeano, Marcello: Lowbrow art / Pop surrealism: Le origini / La storia. Blurb, 2020.

Tuymans, Luc; Kerry James Marshall: “Luc Tuymans and Kerry James Marshall in Conversation”. In: Bomb no. 92, Summer 2005, S. 52-61

Wang, Jiang: “屏幕一代:绘画中的数字考古、写生与革新” [in Chinese]. Hi艺术, March 1, 2024. Translated by DeepL. https://cul.sohu.com/a/761252803_121124789 .

About the author

Haiyu Yuan holds a Practice-Based PhD in Art at the University of Edinburgh. He previously completed an MA in Painting at the Royal College of Art in London (2018-2020) and a BA in Fine Art at Jiangnan University in China (2014-2018). His work has been featured in several exhibitions including: Mad gallery digital exhibition (Milan), Backward Reading (508 Gallery London), Backward Reading (508 Gallery London), Artworks Open2019 (Barbican), Playground V.2 (London), Snapshot (Hockney Gallery London), BP Portrait Exhibition (London), Identity: Flesh, Soul, Time (No Space Gallery/ Online), Fold Gallery: MA Painting of RCA 2020 (London), Phase Transition 2020 (Shanghai), International Young Art Festival (Hangzhou, China), Counter-part Art (Edinburgh), Artworks Open2022 (Barbican).

About this article

Copyright

This article is distributed under Creative Commons Atrribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0). You are free to share and redistribute the material in any medium or format. The licensor cannot revoke these freedoms as long as you follow the license terms. You must however give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. You may not apply legal terms or technological measures that legally restrict others from doing anything the license permits. More Information under https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.en.

Citation

Haiyu Yuan: From Automatism to Bricolage: Exploring Contingency in Surrealist Painting. In: IMAGE. Zeitschrift für interdisziplinäre Bildwissenschaft, Band 41, 8. Jg., (1)2025, S. 48-68

ISSN

1614-0885

DOI

10.1453/1614-0885-1-2025-16546

First published online

April/2025