By Eva Balayan and Lutz Hengst

Abstract

The outside is chaos. The inside is order. Both chaos and order are systems. Order is a system where a third party is able to detect a structure; while chaos is a system that cannot be comprehended. Chaos and order can be described as inside and outside: While the inside is the known area one is able to keep under control; the outside is the unknown as well as the unexpected. Relating this idea to the human body, the latter serves as a shield that protects us from the outside, and which we are convinced to control.

This idea is taken up in the work of Eva Balayan, who engages with the body as a shield or an armour that protects us while being soft, fluid, and unstable. The vulnerability behind the hard rigid shell shows the softness behind the brute defence. The internal substance that the conscious mind is so eager to understand is like a plexus—it grows on its own, spirals out of control, and breaks down the boundaries between systems. These armor-like pieces turn the body that wears them into armor itself. The content starts to grow on the surface in order to hide, to protect and to assimilate. The protection becomes no longer the aim to save what is on the inside, but takes over the main purpose. Defending is existing.

Die künstlerische Prämisse zu diesem Beitrag lautet: Draußen herrscht Chaos und im Inneren die Ordnung. Sowohl Chaos als auch Ordnung können als Systeme betrachtet werden. Ordnung ist ein System, das Übersicht schafft und zum Zwecke intersubjektiver Lesbarkeit von Strukturen, aber auch zur Kontrolle geschaffen wird; Chaos lässt sich dagegen als ein System verstehen, das nicht regelbasiert gelesen werden kann. Werden Chaos und Ordnung als Innen und Außen beschrieben und – insbesondere in instabilen Umwelten und Gesellschaften – so polar erfahren, erscheint das Innere umso eher als der bekannte Bereich, der sich beeinflussen, sogar unter Kontrolle halten lässt. Dagegen kann von außen massiv Unbeherrschbares, Unbekanntes und Unerwartetes einwirken. Wenn man diese Idee auf den menschlichen Körper bezieht, wird dieser potenziell zum Schild, der uns nach außen abzuschirmen verspricht und von dem wir hoffen, ihn steuern und sichern zu können.

Diese Idee wird in der Arbeit von Eva Balayan aufgegriffen, die sich mit dem Körper als Schild oder Panzer auseinandersetzt, der uns schützt, während er eigentlich weich, flüssig und instabil ist. Die Verletzlichkeit zeigt sich hinter der harten, starren Schale, die Weichheit hinter dem manchmal rohen Verteidigungsanspruch. Die innere Substanz, die der Verstand so begierig zu verstehen versucht, ist wie ein Plexus – sie wächst von selbst, gerät früher oder fast unweigerlich außer Kontrolle und reißt die Grenzen zwischen den Systemen nieder. Im Ausgang von den textilen Referenzobjekten Eva Balayans schöpfen sie und Lutz Hengst aus einem ganzen Spektrum moderner wie postmoderner Theorieansätze – um schließlich auch herausgeforderte und entgrenzte Selbstbilder zu reflektieren, die wir uns vom Menschen als körperliches Wesen an der neuralgischen Schnittstelle zu dem machen, was um uns ist.

Introduction

As we enter the year 2025, a time seemingly defined by war, crises, and the resurgence of illiberal political styles even within traditionally democratic nations, engaging with the works of Eva Balayan gives a specific weight to the closing sentence of the abstract “Defending is existing”, which she provides in the context of a small textile art series she presents. Balayan‘s work builds on the observation that the external world is chaos. In contrast to this chaos of the outside world, the human requires a ‘soft’ form of armor. This self-armoring, as Balayan‘s explanations suggest, in her work becomes an autonomous existential end in itself. The idea that such self-armoring can become crucial for survival in the present, given the disorder in the world, seems plausible. In less globally entangled and confusing times (knowing, for example, little of phenomena like forms of pollution affecting the whole world nowadays and, by that, spurring modern or hybrid conflicts), yet in still somewhat rough times for the romantic conception of an ‘emotional artistic community,’ it would have been the external world that was deemed as being too orderly, or perhaps, all too deterministic. The inner world, in contrast, would have been understood as a haven of blossoming heterogeneity, if not productive chaos.

If Balayan’s commentary on her work is read less against the backdrop of the political situation, or the current resurgence of fascist and unchecked capitalist disruptions that are aggressively portrayed in social media, but instead as a formulation of a timeless constellation, other insights emerge. For example, in the following playful, illusion-like basic constellation, one could recognize a partial analogy to a poetic short program coined by Michaela Schmitz for Peter Handke’s early poetry (Schmitz 2008):

“In the interplay of inside and outside, it is primarily about a perception process. The crucial factor here is the change of perspective. That specific double-perspective, which is simultaneously directed towards both the world and the self, the subjective and the objective, the concrete and the abstract. The goal is to explore intersubjectively valid meaning structures starting from self-reflexive knowledge.”

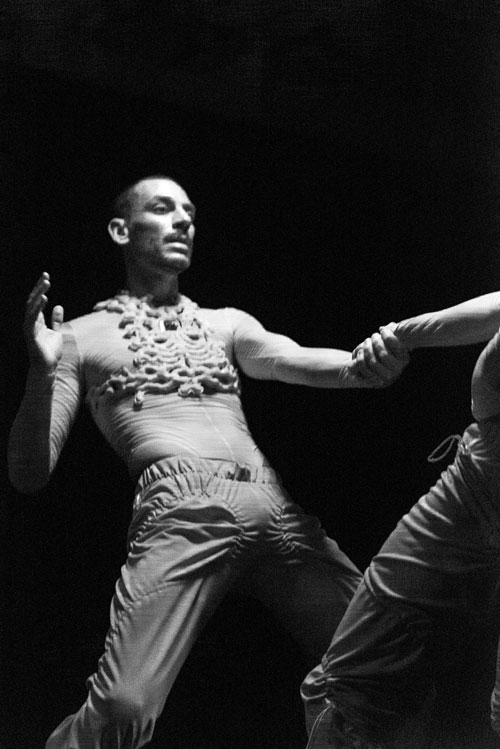

While Balayan’s works continue to negotiate the chronically transitional relationship between subject and object, a reservation remains. It can be seen in an embodiment of the equation of defense and the existence of a (carrier) subject, postulating a limit to the openness for negotiation. Her artworks also suggest that the intersubjective communication of the inner world to a worldly outside, and vice versa, no longer forms an established gravitational center for working on modes of expression (which would still have been associated with an intelligibility-based concept of art). Her armour-like looking, but textile-made objects, which resemble soft but sharply placed exoskeletons—such as protectors for the arteries on the neck—essentially mirror or double the winding physical interior of a person. If fully expanded in detail, it could, in fact, encompass the world and physically exceed the size of a clearly defined individual. The relationship between this renewed emergence of the whole or purely physical in art and larger societal changes need not be fully spelled out or clarified by Balayan’s textile works (as these are works of art and not sheer discourse). Though they are far from textless, the material body textures Balayan shapes can sometimes be so finely crafted that it, resembling coral-like floral bands, instead of proactively covering, rather overspans the wearer’s shoulder blades. In this way, no absolute defense formula is conveyed. Instead, if one who is only protected by additional layers of cloth is capable of turning their back to the world, this must simultaneously be based on a trust in the strength of an aesthetic, a soft defense.

1. Inside the control panel

To describe the mental and emotional state of a being, we can use the allegory of a huge interface resembling an immense control panel of knobs, buttons, pull levers, sliders, and cables that intertwine into a complex system. Like a modular synthesizer, this system sends signals, oscillating between the unusually pleasant and the extremely annoying sounds. To understand where these signals originate, one must first be able to figure out the constantly shifting cable chaos of that platform. In the early stages of life, we resemble a simple sine wave—a relatively unaltered frequency that is sending only a few signals. But as we grow, our environment interacts with this wave, modulating and shaping it in one way or another. While this metaphor applies to a single individual, the same description extends to groups. A collective is its own evolving system, where time and external conditions act as modulators, continuously shifting parameters and generating new dynamic soundwaves.

Within this framework, the problem of individual and collective defence mechanisms can be examined. Defence is a reaction that arises in a response to attack. According to Freudian theory, it is a reaction to protect oneself from the occurring happenings that one could not cope with otherwise (Freud 1926: 97). This same mechanism operates in socio-political context. We engage in defensive action, regardless of whether the occurring changes are indeed damaging or harmless, or we perceive it as something we cannot cope with. What constitutes an attack is subjective, shaped by personal vulnerabilities and one‘s image and sense of self. An individual mind or a collective mind may feel attacked when the foundation of the identity is shaken. Carl Jung could have described this as an encounter with the “shadow self”, when the unacknowledged aspects of the psyche begin to emerge, the conscious self resists because of interpreting this transformation as a threat (Jung 1959: 8). Definition is an important term when it comes to defence. Where the I ends, starts an uncanny valley (Fisher 2016: 98).

2. Endless cloud of particles

In contemporary society, defining the self as fluid has become a significant statement. To those with a rigid belief in fixed identity, this notion may seem absurd. Yet a self that continuously reshapes itself—one that does not fear expansion or contraction—has nothing to defend. It is boundless, like nature. Nature cannot be reduced or expanded; it exists as an all-encompassing hyperobject, hovering above hierarchies like an endless, ubiquitous cloud.

The body, too, is a hyperobject—an entity that emerges, defines itself, and dissolves again into the shifting system from which it came. To humans, it is of immense significance because it is the only transmitter through which we create distinctions, define ourselves and everything around it. It is our sole means of perceiving a separation. As part of this ever-changing, indefinable system, the body is a fluctuation in time and space, momentarily diverging from its surroundings before merging back into them.

A crucial aspect of self-definition is adaptation—the way an entity reshapes itself in response to its environment. Expansion and contraction are fundamental phenomena in nature. Just as the body’s extremities shrink in response to cold, we expand ourselves with layers of belongings to claim space and survive in an individualistic society. Social structures dictate the conditions we must follow in order to fit in. These transformations are not limited to physical appearance but extend into the psychological sphere. The body‘s morphing leaves a profound, even transcendental, imprint on the self. It grants or diminishes power, skills, and beliefs.

Humanity has always experimented with the body’s form. Trends, shaped by the zeitgeist, have stretched, distorted, and redefined bodily ideals to secure acceptance and safety. The adaptation to an idealized shape—whether through garments, rituals, or medical intervention—has long served as a means for concealing aspects of the self. The body becomes a shell, shielding the softer, more vulnerable self from the external world.

3. An e(go)skeleton

Traditionally, an armour was made from metal, designed to protect its wearer from injury or death, allowing them to endure longer in battle. The logic was simple: The side with more surviving fighters would win (regardless of the initial numbers). Mercenaries could also be hired—war was, and still is, a profession. In some countries, military service remains an obligation, forcing individuals to commit to their nation’s defence. The term ‘duty’ is misleading, as it implies choice, yet many are left with no option but to hope they are not born into a country involved in conflict. In some regions, war has become an ordinary state of existence: Meanwhile the main cities are only under economic pressure, and political leaders, often far removed from the battlefield, sit down to negotiate the fate of prisoners of war; someone is defending the borders.

While the best way to stay safe on a battlefield today is to use software with a drone, armour is still in use and has evolved significantly over time. Armour of old times, while primarily functional, was also a canvas for craftsmanship and artistic expression. Basic armour was a simple metal shell, encasing the body for survival. However, some signified status and were considered a sculpture, designed not just for protection but to inspire awe—both among subordinates and enemies. Some were exceptionally ornate, almost delicate, particularly in Italian Renaissance designs—clearly not meant for battlefields soaked in blood, but rather for a contest of greatness. Ancient Greek breastplates exaggerated the idealized male physique, reinforcing the image of strength. Many suits of armor were heavy and cumbersome to wear, but their primary function went beyond practicality: They were primarily psychological weapons.

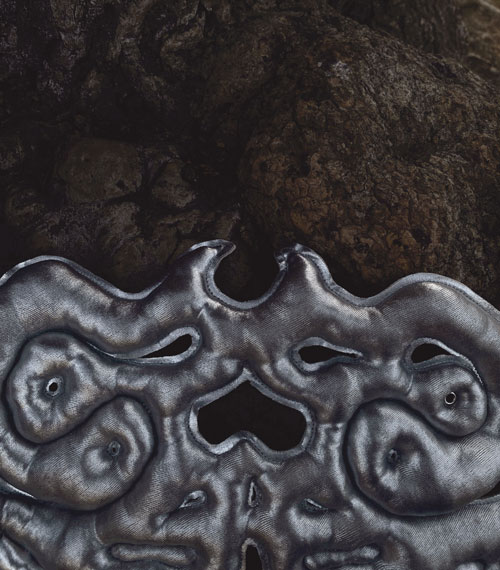

Fig.1: Fragment of a soft armor structure. Image by Eva Balayan, 2024.

For the person inside, the iron or steel shell compensated for its limited mobility by creating a barrier—a fence between the body and the horror unfolding outside. Most armors had masks on their helmets, featuring animal faces or grotesque human grimaces. As masks do, they concealed emotions, allowing fear to remain unnoticed. At its core, armor is a manifestation of the fear of being hurt. Just as the Māori haka dance serves as an intimidation tactic, armor itself is an attitude—an externalization of power, size, and control meant to deter threats.

Today, automated systems handle many frontline tasks, leaving fewer soldiers physically present in combat zones. The most intelligent armor today is not something worn; it is technology itself. The need to eliminate the enemy has advanced to the point where one can sit in a secure bunker, while activating a button. The terrifying element of this protection is no longer the intimidating looks, but the absence of emotions and interaction in total. While the masks replaced the fearful faces of the fighters with frightening ones, a drone has no face at all.

4. Tentacles, roots and rhizomes

The use and distribution of armor depends on the financial situation of both the aggressor and the attacked country. Wealthier nations have access to better technology and materials, while less wealthy nations rely on outdated or improvised protection. Guerrilla groups often sacrifice armor for mobility, using hit-and-run tactics rather than direct combat.

When analyzing global conflicts from a financial perspective, clear patterns emerge as to who tends to be the aggressor and who is being attacked. Due to military superiority and resource interests, wealthier countries are mostly the aggressors, while poorer countries are the ones being attacked. Wealthy nations have played this role for centuries, shaping the global system to maintain their dominance. Attacks are often justified by ideology—diplomacy, communism, anti-terrorism, or national security—concealing private economic interests underneath. This explains how rich countries accumulate their wealth through warfare.

While war can generate short-term economic or political gains, it ultimately leads to instability, resource depletion, resistance, and ecological disasters. Colonial economies are structured to extract resources for the benefit of the colonizer, not the local population. Later, generating income from a former colony becomes difficult, as it remains economically and socially dependent on the colonizer. War and colonization are losing strategies in the long term, as they create short-term power but result in long-term instability, which inevitably cycles back (cf. Latour 2017: 17).

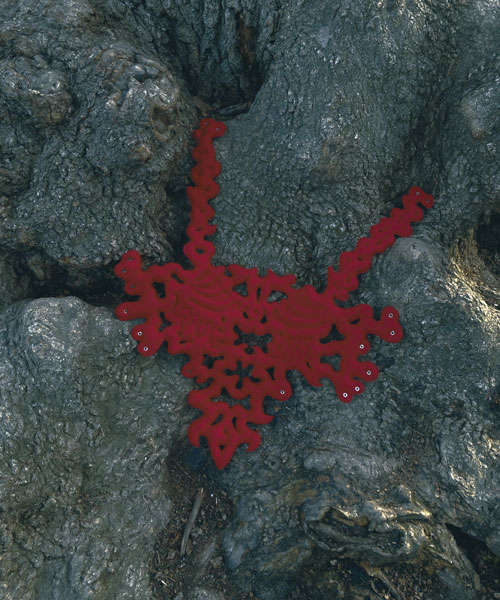

Fig.2: Soft armor. Image by Eva Balayan, 2024.

When short-term benefits are prioritized, we root ourselves in synthetic soil from which one can easily be pulled out. Not only do we separate ourselves from nature, but we also detach from one another, categorizing everything into groups and hierarchies. This centralized, fractal-like growth is unstable—especially when its base is already dry and unfruitful. In contrast, rhizomatic growth creates multiple points of mutual strength, distributing development more proportionally. Sharing knowledge and investing in balanced growth fosters sustainability and security.

We often perceive everything around us as a resource to be claimed and made useful. But instead of hoarding, creating interwoven benefits offers real safety. Even our bodies are vessels over which we have no full control. From the perspective of life and death, early beliefs suggest that materialism has always created an existential crisis. Some ancient burial traditions involved not only the transfer of material goods and the preservation of the deceased bodies for as long as possible, but also the projection of entire social hierarchies into the underworld.

The anxiety of losing one‘s possessions and the status acquired during a lifetime is directly proportional to those possessions. This is reflected in the choice of fabrics and materials used to lay a body into the ground for decomposition. Since no one is present to appreciate opulence underground, the motive is not merely to display social rank, but rather stems from the assumption that the other world mirrors this one—and that loved ones want to send the departing soul off in the finest equipment.

On the other hand, there are beliefs that see the body as a temporary vessel for the soul (which raises the question: Is there a soul without the body?). These traditions emphasize leaving the body behind sustainably, without leaving unnecessary traces. In Zoroastrian burial traditions, all people are considered equal after death. Their remains are no longer individual, and all are treated the same. After death, the clothes wrapping a body no longer signify status. The absence of ownership eliminates the fear of loss. Leaving the body to the environment is the final trade we make with nature and its resources.

Understanding that even during life the body is part of the environment is a crucial step toward dismantling the barriers of ownership. In this light, the concept of threat becomes irrelevant. Instead of defending our belongings by destroying a suspected wrecker, the focus shifts to sustaining the longevity and prosperity of the sources that sustain us.

The idea of communal ownership has been promoted many times in different forms by such thinkers as Erich Fromm or Karl Marx, and various solutions have been proposed. Yet the world continues its cyclical patterns, shifting only slowly toward different ways of thinking. The destruction caused is disproportionate to the repair, and since our own lives are not fully in our hands, single individuals struggle to make a significant impact. For this reason, it makes sense to avoid prescribing a grand solution to global change—only to suggest that we remain aware of these dynamics in our decisions and in our dealings with each other. We should seek and share sympathy with each other, whatever our views on life are on an everyday basis. Like a living organism, in which all the tissues work together to support the body, like an organic matter, everything has come together to reproduce from itself.

***

I spent a lifetime designing my nest and it will never be done. Once I think it is ready, the circumstances shift and I must start redesigning it. I reshape my nest so often that it becomes unrecognisable, nearly losing its original function. I wish I could stop adopting it and cope with the harsh conditions. No matter how horrifying it will become, at some point the nest will be ready. Maybe I no longer will be present, but my nest will persist and become a host to others, nurture them until they, too, leave. But for now, I try hard to protect myself from outside invasions. I am in my nest and the outside is scary. But what shall I do if I get the feeling of becoming an invader to my own home?

The insides of the nest are soft and warm. They lead me towards the softness and warmth of the other. I constantly look for it inside and outside. When my inside is so undefinable, no one can attack it. Letting go of my defined forms, lines, terms, textures, I become an ooze that cannot be penetrated and is penetrated all the time.

Here am I, with my soft single breast out, all eyes turned away from me, for my vulnerability is vulgar. On the rigid cold ground I let all the body liquids flow – they start dripping from my eyes, every single hole my body has, every single pore and gland. My inside will grow through the skin, cover it with its fibres and assimilate it. Sitting next to one another, our pores will softly touch, exchanging minerals and bacteria, soothing pain and liquifying each other into one. We dissolve and become a self-embracing-soup that knows no fear and danger, but makes everyone around feel a little uncomfortable.

“I’m not owning, I’m renting – The body as a place to stay”

part of the artistic research writing for the work “Soft Armour” by Eva Balayan

5. Porous divinity

The world around us can be understood as a system that provokes forms and protection, in which we are involuntarily integrated physically, mentally, and socially, and to which we incessantly react, not least through our textile cultural expressions. And while the world is changing, every transformation provokes new or at least renewed forms. Yet, from the perspective of frameworks that are familiar to and manageable for us, change appears as a universal principle: endless streaming, colliding, reacting, mixing, recombining, and diffusing. The universal world, when viewed in this way, confronts entities that are defined according to dominant human perception and biological definitions as potential power, which is reabsorbed into the great flow of all elements. In this regard, ‘stream’ seems to be a more fitting term compared to ‘river’ or ‘flow’. The modern idea of a ‘fluid identity’ is characterized by a more fluid transition from one self-concept to the next, compared to rigidly defined identity concepts. The self or non-self positioned above this, which does not need to defend itself because it is always flowing along, would have no defined identity contour, not even one in the process of flowing. It would be oriented towards flowing together, for which a riverbed, with its inherent stability, would be an inadequate metaphor, suggesting too much stability.

It is remarkable at this point that such identity metaphors refer back to ancient formulations of a principle of comprehensive fluidity, famously captured in the formula Panta rhei, often attributed to Heraclitus. Furthermore, they also appear in the midst of advanced modern thinking, particularly in the 20th century, as seen in the work of Martin Heidegger. Despite his ideological entanglements during the time of National Socialism, his thinking remains an important reference point, even for postmodern identity concepts (prominently, for example, in Michel Foucault’s writing). It is particularly attractive for our context here that in one of Heidegger’s smaller works, the lecture “Building Dwelling Thinking”, the image of a river plays a central role (cf. Heidegger 1971). In it, the river functions as a kind of embodiment of free nature. However, it is only by spanning the pure natural phenomenon of the river with a bridge that the river, according to Heidegger, becomes an entity shaped by the surrounding landscape. This spatial figure resembles the image Heidegger creates in “The Origin of the Work of Art” by juxtaposing a closing earth on one hand and the unclenching world on the other. Again, it is architecture that provides something of a boundary. Instead of a bridge, this time a temple enables the earth to become the world, in the sense of a place understandable to humans (cf. Heidegger 1995: 37ff.). Seen in this way, what human subjects protect themselves and their lives against is not the world but the earth and its cosmic openness. Additional psychoanalytic metaphors are not even needed to explain that an infinitely open perspective must appear as an exposure to the shieldlessness for the drive to maintain a definable self.

The uncanny nature of this perspective is always present, but today, another dimension is added: the incessant flow of digital data. Although this is maintained only by physically channeled energy and devices that consume rare earth materials, it seems to further challenge the boundary between the physical self and its environment, plus now the virtual cosmos. On the other hand, it is becoming increasingly important to strengthen the body, to enhance and protect our sequenced individual inner core at sensitive points. In addition to the function of the extra layers that arch over the body, analogous to Heidegger’s temple, in keeping it legible as a world in itself, they also resist the potential of being scanned without resistance. If this is not opposed, the boundary to the virtual environment becomes potentially porous, with no clear separation between inside and outside.

6. Flattering camouflage

Camouflage allows an organism to bypass danger simply by blending in, avoiding harm without confrontation. Many species have evolved to resemble their surroundings or even adapt their appearance in real time—shape shifting as a survival mechanism. Yet in a society that rewards visibility, invisibility becomes a paradox. The more one is noticed, the more one becomes a target, and vice versa—inimitability is highly valued.

Another common survival strategy is repulsion. A threatening appearance, an overwhelming scent, or an unsettling sound can repel potential threats. But within the framework of social acceptance, such tactics often backfire. Rather than intimidating, one must attract. Camouflage, in this sense, is not about disappearing but about adapting in a way that flatters—inviting inclusion rather than rejection.

This principle extends into clothing. The first association with camouflage is often military attire, designed both for concealment and authority. Military fashion has long influenced civilian dress, shaping not only men’s wardrobes but also women’s garments (Fussell 2002: 174). While protection and invisibility serve primal, utilitarian needs, flattery serves the purpose of surpassing an opponent, fulfilling complex egocentric needs. Historically, colors, fabrics, and insignia have signified rank and status, distinguishing friend from foe, soldier from civilian, elite from the ordinary.

Camouflage today is no longer just about blending into the background, but about embedding oneself within a system of distinction. Modern clothing carries obvious elements of this ranking system—emblems, logos, and branding act as status markers, certifying the social position of the person covered with them. In this sense, humans are not only camouflaged but categorized, wrapped in layers of coded identity.

7. Instinctive biting

Defense and adaptation to harsh environments have shaped the development of all living organisms. Some have evolved the most creative ways to protect themselves and preserve their DNA. Beyond the well-known fight-or-flight mechanisms, certain species avoid attacks through camouflage, temporary death, or even strategic cooperation with other deadly organisms—such as the acacia plant, which ‘hires’ aggressive ant species to defend it against predators (Unger Baillie 2019).

Preemptive elimination is a strategy mostly adopted by animals with the largest brains and/or advanced social structure. While some species have developed the instinct to kill potential predators before being attacked, others go further and eliminate members of their own species who might threaten their position in the hierarchy. Humans are undoubtedly one of these species, and our methods of neutralising competition have far surpassed those of any other life form. Forced sterilisation, stand-your-ground laws, political purges, war, and genocide have all become established strategies to „protect“ against perceived threats and optimise living conditions. Not only have we refined the act of elimination, but we have also built a complex infrastructure around it—systematising it through ideologies, propaganda, and technology to justify preemptive killing on a massive scale. The large brain and intricate societal structure, group coordination, and environmental pressures—result in increasingly desperate and brutal problem-solving tactics.

But strangely enough, the antique idea of humans being at the pinnacle of all races does not make a human being fulfilled. Since we do not merely function on instincts, we developed ideologies that are against violent solutions. We rationalise the brutality of our defence mechanisms, but at the same time, violence is deeply condemned within society. On the other side of our cognitive and social inferiority is the desire for altruism and empathic behaviour. In contrast to other species, humans have also excelled in non-destructive emotions such as trust, sympathy, and guilt, counterbalancing primal instincts like fear, skepticism, and aggression. Of course, these emotions are related, but trust and compassion often emerge only after one has moved beyond the instinctive, survivalist mindset, demonstrating that they are a step beyond the previous desperate reaction.

Creating a parallel to this, one might consider the separation of humans from their environment a crucial point of vulnerability—when survival skills became mostly based on creating a society and being part of it, fitting in and adopting, individuals now are becoming fully emerged by the infrastructure and technology, leaving little place for independence and self reflection. The transition from being naturally equipped to requiring external protection, such as clothing, may have psychological implications. The act of covering oneself can be seen as a response to vulnerability, both physical and emotional. This need for protection might contribute to a heightened awareness of one‘s fragility, potentially leading to behaviors aimed at asserting control or dominance to mitigate feelings of insecurity. Clothing serves not only as physical protection but also offers symbolic protection against psychological threats. Research indicates that attire can shield individuals from the emotional consequences of existential threats, providing a sense of security and identity during crises (Gruber/Kachel 2023).

The theory of “enclothed cognition” (Adam/Galinsky 2012) suggests that the clothes we wear can influence our psychological processes. For instance, wearing certain garments can affect our self-perception and behavior, potentially serving as a means to assert control or mitigate feelings of insecurity. The cult of masquerade and festive costumes during celebrations have marked the culture in every region. The experience of being in animals’ skin provides qualities the wearer does not have without it. In some cases the costume wearer acquired skills or qualities only when wearing the costume, like strength or speed, as if the muscle structure is changing once a special additional layer is covering the skin. While the armour is providing a function of protecting the body from damage, it is also capable of giving supernatural skills that only the human wearing it can activate. In fact, with autosuggestion—a technique in which a person can train their subconscious mind to accept certain beliefs by repeatedly affirming them, anything can become a powerful item. A curious example are the necropants—according to Icelandic legend, a sorcerer could gain endless wealth by wearing nábrók-pants made from the skin of a dead man. After making a pact during the man’s life, the sorcerer would exhume the body, flay the skin from the waist down in one piece, and wear it. To activate the magic, they had to steal a coin from a poor widow and place it, along with a magical stave (nábrókarstafur), into the scrotum. This was believed to make coins appear endlessly.

8. Globalised paralysis

Despite the creation of a highly complex social infrastructure connecting millions of individuals around the globe, people tend to live individualistic, privatised lives rather than unite in communities. The reaction to globalisation tends to be a denial of connectedness. Capitalism and owning property, the possessive limitations are probably reasons for such reactions. Despite our cognitive evolution, we now find ourselves retreating, not into fortified strongholds, but into individual, private realms, that work systematically, turning away from the organic structures we might build. The rise of individualism, particularly in Western societies, has been linked to the erosion of communal ties and a retreat into private life (Rapti 2018).

National defence no longer exists solely for the sake of protecting a society and its prosperity, but rather to manipulate the interests of certain individuals and their environment. The enemies and allies are defined by budget and opportunity. At the expense of environmental and social stability, the defence has taken a convoluted form and is often the subject of conspiracy theories. With the information cataclysm—the overflow of real and fake news, the interest in investigating and finding the truth is a great challenge. The lack of control and the inability to influence the state of things in one’s life has created a great disconnect between the individual and society. Globalisation makes it invisible and unnoticeable, and we all slowly dive into a hedonistic future, covered with a bulletproof glass that only shows the part of the skies that looks sunny.

9. Open source ego

Moths are covered in fur because they fly at night and their main predator are bats that use sound waves to hunt. The fur muffles the sound and keeps the moth safe. In addition, their wings are textured with giant eyes to keep the predators away. Moths have no teeth, no claws, no horns, but a personality and a rhythm. Thewy will live only a few short days to love and to mate. They live for a short time, but have a meaningful life. (Unknown)

In conclusion, for a society to be open about insecurities fosters deeper trust and reduces conflict. This principle is evident in interpersonal relationships, particularly in conflict resolution. In couple therapy, for example, partners are often encouraged to share their fears and vulnerabilities. In long-term relationships, conflicts arise because individuals instinctively become defensive—despite the fact that their relationship was originally founded on mutual desire. Each partner tries to protect their boundaries from the other, sometimes even sabotaging the relationship to preemptively avoid potential heartbreak.

When we share our insecurities instead of constructing a facade of invulnerability, we send a powerful message: We are unarmed, unprotected, and willing to expose our weak spots. This openness can be intimidating, because it requires extreme confidence and courage. It transmits trust, and in most cases, people who are entrusted feel responsibility to reciprocate. Moreover, it is easier to form genuine bonds when we share our struggles rather than boast about our ability to handle every crisis. Failure and misfortune are universal experiences, and expressing them makes it easier for others to sympathise.

Psychotherapy teaches us to define and defend personal boundaries. However, we should first learn to respect the absence of boundaries. Imagine a garden: If you wish to enter, how does your attitude change if you are faced with a high fence, an open gate or no fence at all? The absence of a barrier is often taken for granted, while exclusivity is perceived as more valuable. This is why we must learn to appreciate unrestricted openness, rather than the privilege of being invited into an exclusive space.

A truly open-source societal model, in which individuals freely share their struggles without fear of judgment, could prevent defensive reactions that escalate into conflict. Admittedly, this is a utopian vision that may never be implemented in our chaotic reality. However, meaningful change can only begin at the individual level. Capitalism, economic crises, and the threat of war have numbed the Western world to the limited pleasures of consumerism. Mistrust is often the basis of every social structure, from personal relationships to governmental systems, leading us to be armed with possessions against all possible threats. Despite this instinct to protect ourselves, we can still move forward, gradually, step by step, one by one, generation by generation, replacing fear-driven aggression with awareness, sincerity, and genuine solidarity.

10. Exhale

I do not know exactly how, but I will have to restructure my infrastructure, my economy, and my systems. My political models are attempts either to impose or avoid certain limitations of my human existence. But rather than nurturing my fundamental needs, these systems often suppress my individuality, molding my identity to fit an overarching structure, instead of allowing it to flourish.

Progress is important, and unity is crucial to it, but in my society, the goal has become unconscious. While my body longs for something different, I push myself toward a singular aim that never truly will satisfy me. My body speaks, and my mind should listen. Yet I impose rigid rules, dictating who I must be, monetizing my lifestyle and ideas, and forcing my time into artificial frames, shaping myself into something prescribed rather than something organic.

Since strong societal bonds often encourage impulsive, reactionary behavior, change can only happen if I build a structure, an open-source fabric of values and systems, that remains adaptable even when circumstances become difficult. My society does not cling to rigid definitions, but instead evolves, staying transparent and receptive, even in the face of crisis.

Fig.3: Costume for „Seismic“ performance by Herwig Scherabon and Tanja Saban. Image by Sophie Christ, 2022.

Some tickling sensation makes my skin dry out, covering it with red and brown dots. My hair falls out and grows back like a waterfall. Looking at my palm, I see my skin rising and trembling from within. Terror fills my eyes—my skin wants to leave me, to abandon me, leaving me dry and turning to ash. I kiss it goodbye and watch as it crumbles away, leaving me completely naked. SCARY. Scarier to look at than to be. In the end, we all shed our skins. And this is beautiful.

“I’m not owning, I’m renting – The body as a place to stay”

part of the artistic research writing for the work “Soft Armour” by Eva Balayan

Literature

Adam, Hajo; Galinsky, Adam: Enclothed Cognition. In: Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48(4) 2012, pp. 918–925

Fisher, Mark: The Weird and the Eerie. UK: Repeater 2025

Freud, Siegmund: Inhibitions, Symptoms and Anxiety. New York [WW Norton & Company] 1926

Fussell, Paul: Uniforms: Why We Are What We Wear. New York [Houghton Mifflin Company] 2002

Gruber, Robert and Kachel, Sven: Dressing through crisis: Examining clothing’s symbolic protection from the psychological consequences of existential threats using the example of the COVID-19 pandemic. In: HENZLER, I.; HUES, H.; SONNLEITNER, S.; WILKENS, U. (eds.): Extended Views: Gesellschafts- und wirtschaftswissenschaftliche Perspektiven auf die Covid-19-Pandemie. Vienna [Böhlau Verlag] 2023, p. 105–117

Heidegger, Martin: Building Dwelling Thinking (Poetry, Language, Thought, translated by Albert Hofstadter.) New York [Harper Colophon Books] 1971, n. p.

Heidegger, Martin: Der Ursprung des Kunstwerks. Stuttgart [Reclam Verlag] 1995, p. 37–39

Jung, Carl G.: Aion: Researches into the Phenomenology of the Self. Vol 9, part 2. New York [Princeton University Press] 1959

Latour, Bruno: Down to Earth: Politics in the New Climatic Regime. Paris [Polity] 2018

McNeill, Will: Care for the Self. Originary Ethics in Heidegger and Foucault. In: Philosophy Today 42(1) 998, pp. 53–64

Rapti, Maria: Globalisation and individualism: Implications for the inclusion agenda. In: The British Educational Research Association, 5.06.2018. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326037603_Globalisation_and_individualism_Implications_for_the_inclusion_agenda (22.04.2025)

Unger Baillie, Katherine: The Mutualistic Relationship Between Ants and Acacias. In: University of Pennsylvania, 2019. https://omnia.sas.upenn.edu/story/mutualistic-relationship-between-ants-and-acacias (20.4.2025)

Schmitz, Michaela: The Inner World and Outer World. In: Deutschlandfunk, 24.03.2008. https://www.deutschlandfunk.de/innenwelt-und-aussenwelt-100.html (20.04.2025)

Biographies

Eva Balayan (b. 1991, Yerevan, Armenia) is a Vienna-based media artist with a background in digital art and design. After moving to Austria in 2006, she studied Graphic Design in Graz and later Digital Art at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna, completing her diploma in 2023 on the erasure of cultural identities in conflict zones. 2021 she expanded her practice through illustration studies at the University of the Arts in Berlin. Her practice combines visual digital media with physical, traditional objects. She explores tradition and heritage in relation to self-perception, with a strong interest in identity and communication across both digital and physical spaces. Her works often take the form of multimedia objects, frequently accompanied by theoretical essays. She has exhibited in Vienna, Vilnius, Aveiro, Berlin, and Los Angeles.

After studying European ethnology, art history and historical geography, Lutz Hengst was first a scholarship holder of the International Graduate Centre for the Study of Culture (GCSC) and then a research assistant for art and design history at the University of Wuppertal. He then completed the mediator training for documenta 13 and was subsequently, from 2012 to 2019, a research assistant at the Berlin University of the Arts and, from 2019 to 2022, a postdoctoral researcher in the DFG Centre for Advanced Studies Imaginaries of Power at the University of Hamburg. Since 2022, he has been Professor of Theory and History of Art, Design and Aesthetics at the Academy of Fashion Design Berlin and since 2024 also Vice Dean for Research in the Department of Design at the Fresenius University of Applied Sciences. His research focuses, among other things, on questions of space and materials in the modern arts.

About this article

Copyright

This article is distributed under Creative Commons Atrribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0). You are free to share and redistribute the material in any medium or format. The licensor cannot revoke these freedoms as long as you follow the license terms. You must however give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. You may not apply legal terms or technological measures that legally restrict others from doing anything the license permits. More Information under https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.en.

Citation

Eva Balayan; Lutz Hengst: Soft Armour: an open source defence mechanism. In: IMAGE. Zeitschrift für interdisziplinäre Bildwissenschaft, Band 42, 8. Jg., (2)2025, S. 225-241

ISSN

1614-0885

DOI

10.1453/1614-0885-2-2025-16671

First published online

September/2025