By Ruth Eaton

Abstract

The pocket, often the subject of gendered discourse and production, is both celebrated and maligned, particularly in relation to disparities in the size and functionality of pockets in men’s and women’s clothing. Prompted by a personal experience of newfound mobility after childbirth, this paper interrogates the gendered dimensions of pocket design and explores how such everyday features reflect broader norms around autonomy, access, and embodiment. Focusing on pocket memes posted by Twitter users between 2019 and 2021, the study employs a social listening approach (cf. Stewart/Arnold 2018) to analyse both the memes and their related commentary. Drawing on Partington’s interpretation of intertextuality, which posits that meaning is generated through the viewer’s relationship with images/objects rather than the inherent properties of the images or objects themselves (cf. Partington 2013: 15). These digital artefacts are understood not as isolated images, but as part of a complex interplay of intertextual references that reflect and shape user experience.

This paper explores how participatory practices of sharing and consuming memes can facilitate online co-creation. Specifically, it investigates the role of memes featuring pockets, in communicating wearer experience of clothing pieces. The aim here is to highlight the potential of meme culture as a form of participatory commentary that reshapes perceptions of such everyday objects like the pocket. By combining insights from dress history, digital media, and feminist critique, this research demonstrates the value of social listening in understanding the intertextuality of memes from the perspective and experience of the consumer.

Die Tasche – häufiger Gegenstand geschlechtsspezifischer Diskurse und Produktion – wird sowohl gefeiert als auch verunglimpft, insbesondere im Zusammenhang mit Unterschieden in ihrer Größe und Funktionalität als Accessoire von Männern und Frauen. Veranlasst durch eine persönliche Erfahrung neugewonnener Mobilität mit Neugeborenem, untersucht dieser Beitrag die geschlechtsspezifischen Dimensionen des Taschendesigns und erkundet, wie solche alltäglichen Bestandteile umfassendere Normen von Autonomie, Zugang und Körperlichkeit widerspiegeln. Die Studie konzentriert sich auf Pocket-Memes, die von Twitter-Nutzern zwischen 2019 und 2021 gepostet wurden, und verwendet einen Social Listening-Ansatz (vgl. Stewart/Arnold 2018), um sowohl die Memes selbst als auch die dazugehörigen Kommentare zu analysieren. In Anlehnung an Partingtons Interpretation der Intertextualität, die davon ausgeht, dass Bedeutung durch die Beziehung des Betrachters zu Bildern oder Objekten und nicht durch deren inhärenten Eigenschaften erzeugt wird (vgl. Partington 2013: 15), werden diese digitalen Artefakte nicht als isolierte Bilder verstanden, sondern als Teil eines komplexen Zusammenspiels intertextueller Bezüge, die die Erfahrungen der Nutzer widerspiegeln und prägen.

Im vorliegenden Beitrag wird untersucht, wie partizipative Praktiken des Teilens und Konsumierens von Memes kollektives Online-Kreieren erleichtern können. Konkret wird die Rolle von Taschen-zeigenden oder zumindest -behandelnden Memes bei der Vermittlung von Erfahrungen des Kleidertragens erforscht. Ziel ist es, das Potenzial der Meme-Kultur als eine Form des partizipativen Kommentierens hervorzuheben, das die Wahrnehmung von Alltagsgegenständen wie der Tasche verändert. Indem Erkenntnisse aus Modegeschichte, digitalen Medien und feministischer Kritik kombiniert werden, demonstriert dieses Forschungsprojekt den Wert des Social Listening für das Verständnis der Intertextualität von Memes aus der Perspektive und Erfahrung ihrer Konsumierenden

1. Introduction

My preoccupation with pockets began after the birth of my first child. Beyond the figurative burden of carrying the weight of others’ expectations, pregnancy itself is a literal embodiment of supplementation (cf. Bari 2019: 107). The pram, my new indispensable companion, marked a pivotal shift. It not only transported my child safely but also bore the physical load of everything I once carried on my body. I experienced a kind of embodied freedom: My hands were unencumbered, my movement less restricted, aside from steering the pram, of course. This experience prompted a simple but profound desire, to continue moving through the world with my hands free. In this pursuit, pockets emerged not just as practical features, but as enablers of autonomy and mobility. In reflecting on my experience, I began to question the broader implications of pocket design: How might such a seemingly mundane feature reflect and reinforce social norms, particularly around gender?

The design and inclusion of pockets in clothing have historically been found to reflect societal gender roles, with women’s clothing often lacking functional sewn-in pockets or omitting them entirely. This disparity not only marked a material difference in clothing but symbolised broader inequalities in autonomy and access, with women‘s restricted pocket space mirroring limited access to money and property. Some men also expressed dissatisfaction with pocket functionality (cf. Matthews 2010) and conversely, some women found their pockets sufficient (cf. Burman 2002). However, the pocket remains an object that signifies gendered differences in fashion. The historical accounts revealed that pockets have long intersected with gendered expectations and practical concerns, but there are limited studies of contemporary pockets, particularly from a wearer perspective. The present paper addresses this gap in research.

Memes have emerged as potent tools for participatory culture, enabling users to co-create meaning and critique everyday experiences through common experiences, interests, or humour. Richard Dawkins originally defined a meme as “a unit of cultural transmission or unit of imitation” (Dawkins 2006: 192), but this definition has developed and adapted alongside the internet and social media. For example, a more relevant description from Mitman and Denham is that memes are forms of “collective, networked, pictorial, and caption humour and social commentary, as well as cultural labour” (Mitman/Denham 2006: 1). Also central to this research is the concept of ‘intertextuality’. In fashion- related posts, for instance, the meaning of an outfit isn’t simply “read off” the clothes themselves. As Partington argues, fashion’s significance isn’t embedded in garments alone but is actively produced by consumers who combine clothing with other cultural elements to construct class-specific or subcultural meanings (cf. Partington 2013: 8). Thus, on social media, intertextuality becomes a way that people signal taste, align with certain cultural groups, and shape their online identity, not by inventing new meanings from scratch, but by remixing existing cultural material. Intertextuality is therefore a fundamental attribute of the internet meme, from this point referred to as a ‘meme’, and integral to contemporary digital culture (cf. Shifman 2014: 2).

The experience of the persistent gender disparity in pocket design can be seen frequently in online commentary, also highlighted through the circulation of pocket memes. In the context of pockets and gendered clothing, memes serve as concise representations of collective experiences and emotions, ranging from frustration and anger to joy. The act of commenting on and resharing these memes further amplifies participatory commentary, that underlie meme culture, or the “day-to-day online engagement” (Bardos 2023: 18), and which collectively reshape perceptions of everyday objects such as the pocket. The intersection of memes and online social commentary on Twitter (prior to rebranding as X) is explored through a “social listening” approach, which is defined as “an active process of attending to, observing, interpreting, and responding to a variety of stimuli through mediated, electronic and social channels” (Stewart/Arnold 2018: 96). The analysis examines the ways in which consumers forge intertextual relationships between their lived experiences with clothing, pockets, and online communication.

Online participation relies on the voice or the activity of the user (cf. Crawford 2009: 526). So it is potentially the user who shouts the loudest, posts most frequently or virtually tags other users to attention (e.g. with tags and hashtags), who is heard first. This notion of visibility begs the question about privilege and power: Who can speak up, or be heard? It informs the social listening approach, which is to listen to both the active and silent participants, an opportunity that has not been fully addressed in social media research (see Adjin-Tettley/Garman 2023; Crawford 2011, 2009). Social listening is employed through the parameters of defined data events on Twitter, to mirror the way in which social media content is consumed by users, guided by Partington’s interpretation of “intertextuality” which posits that meaning is generated through the viewer’s relationship with online images/objects rather than the inherent properties of the images or objects themselves (cf. Partington 2013: 15). The study investigates the mechanisms by which users engage with and reinterpret the Twitter content, examining the ways in which online content operates as a discursive lens through which emergent and collectively negotiated meanings surrounding the gendered experience of pockets are articulated. This research therefore extends the work of dress historians by using the intertextual pocket and the pocket meme as a method of investigation to present the contemporary position of the gendered pocket.

The gendered nature of the pocket is first examined in order to contextualise the pocket meme within the broader discourse surrounding gendered clothing issues and their societal impact. The paper will then highlight the relevance of memes, defining the key terms and concepts that inform the analysis. Then, combining these conceptual and practical considerations, three pocket meme case studies will be presented and analysed. This analysis examines how the temporary online community of Twitter users engage with and reinterpret the pocket meme content, offering insight into how the intertextuality of memes reflects user perspectives and collective experiences of the gendered pocket. Finally, the implications of the findings will be explored, highlighting the key themes identified via the pocket memes and related Twitter threads.

2. The Pocket as a Gendered Object

This research situates the pocket as a gendered object by drawing on foundational dress and fashion theory that views clothing as a communicative and culturally embedded practice. Scholars such as Wilson and Taylor (1989), Roach Higgins and Eicher (2002), and Skov and Melchoir (2008) argue that bodily adornment reflects and reinforces social norms, including those related to gender, class, and power. These theoretical frameworks enable an interrogation of the pocket not as a trivial design feature, but as a meaningful site of cultural negotiation.

Historical literature reveals a consistent omission or reduction of functional pockets in women’s clothing, a design trend that has material consequences for social mobility and independence. As Burman asserts, “the pocket can be situated as a significant gendered object in nineteenth-century Britain” (Burman 2002: 447). This disparity is echoed in Matthews’ visual analysis of Victorian art, where he describes men as “naturally pocketed creatures” (Matthews 2010: 561) and suggests that women were systematically denied this feature as part of a broader ideological containment of female agency. In her study of Victorian literature, Fitch characterises the pocket as “a small and overlooked object” (Fitch 2017: 16) that nonetheless plays “a pivotal role in cultural behaviour” (ibid: 25). Myers’ investigation into rational dress and the New Woman movement further illustrates the symbolic threat posed by the adoption of integral pockets in women’s fashion. According to Myers, the emergence of functional pockets in women’s clothing was seen as a direct challenge to patriarchal structures, prompting a return to decorative, non-functional alternatives that reinforced traditional gender roles (cf. Myers 2014). Beyond functionality, the pocket also serves as a site of resistance and subversion. The continued use of tie-on pockets by women functioned as resistance to the fashion mainstream, maintaining a degree of independence through concealment (cf. Burman 2002). Similarly, Sampson identifies hidden storage in garments, such as pockets, purses, and bags, as central to personal autonomy, particularly in the context of limited female social mobility (cf. Sampson 2024). This subversive potential is reflected in Talcott’s concept of the pocket schema, which he argues opens philosophical and political space for subjectivity. While his analysis primarily focuses on male usage, he acknowledges that secret pockets enabled women to perform acts of ambiguous resistance, such as shoplifting, thereby disrupting dominant gendered expectations (cf. Talcott 2024). Such practices are linked to early twentieth-century consumer cultures in which concealed pockets became tools for both survival and symbolic defiance (cf. Burman/Fennetaux 2019).

The fashion industry has historically reinforced gendered distinctions through pocket design. Christian Dior’s now-famous remark, „Men have pockets to keep things in, women for decoration“ (Johnson 2011), reflects a longstanding design ethos. In his Little Dictionary of Fashion (1954), Dior describes pockets in women’s clothing as elements of visual interest, meant to „emphasize form, add detail and colour“ (Dior 1954: 90), with the only functional mention being that they provide a place to put one’s hands when feeling awkward. Notably absent is any reference to carrying belongings, a silence that underscores the ornamental role prescribed to women. This ethos potentially filtered into mainstream fashion through the trickle-down effect, influencing ready-to-wear and home-sewn garments. The result was an inconsistent pocket provision in women’s clothing. In The Book of Pockets, Gorea et al. note that fast fashion has led to pocket elimination as a cost-cutting measure. Yet this explanation implicitly transfers responsibility to price-driven consumers rather than interrogating the structural gender biases embedded in design choices (cf. Gorea et al. 2019: 196).

Beyond utility, the pocket also carries symbolic and emotional weight. Bari describes the pocket as a kind of companion, protective yet fallible, capable of safeguarding treasured items or failing in moments of need. She writes, “Sometimes, a pocket makes a fool of us… But at its best, the pocket possesses a certain magic. It supplies the gun, the stolen key, the gold coin… It is full of promise” (Bari 2019: 108). Such language frames the pocket as both materially and psychologically significant, with its absence experienced as a loss of potential and power. The gendered dynamics of pocket design remain present in contemporary fashion discourse. Popular critiques continue to voice frustration over the lack of functional pockets in women‘s garments (cf. Parkinson 2019), linking this absence to broader issues of economic independence and embodied freedom. While accessories like handbags may provide alternatives, they do not substitute for the embodied practicality of integral pockets.

Pockets allow wearers to move through the world hands-free, facilitating independence and self-sufficiency. Their absence, especially when persistent and gendered, reflects a deeper imbalance in the ways society expects different bodies to engage with public space, responsibility, and mobility. The pocket is therefore more than a utilitarian detail; it is a deeply gendered site of cultural meaning, historical resistance, and contemporary frustration. Through its form, function, and symbolic weight, the pocket reflects enduring disparities in how clothing mediates social mobility, power, and identity. Attending to the pocket, and its absence, offers a compelling entry point for interrogating the subtle but powerful ways gender operates through design.

3. Memes, Meanings and Intertextuality

Rather than mere entertainment, memes reflect everyday communication and facilitate the sharing of cultural knowledge, making them valuable for understanding user perspectives. Partington’s (2013) intertextuality, where meaning is not fixed in the meme itself but emerges through its reception and adaptation by audiences, is particularly relevant to pocket memes, where a single image or phrase is continually reshaped through layers of shared cultural knowledge, commentary, and humour. Partington highlights the value of analysing fashion content intertextually from the consumer’s perspective, a view expanded by positioning memes as both cultural artefacts and methodological tools in qualitative research (cf. Iloh 2021: 1). Holm similarly asserts that meme creation and circulation are embedded in participatory culture, underscoring their social and communicative functions (cf. Holm 2021: 12). Together, these perspectives support the view that memes offer rich potential for academic inquiry, particularly in exploring how shared digital expressions can produce insights into gendered experiences within dress and fashion.

Twitter provides further potential for the meme’s communicative function as a tool for cultural expression through the mechanisms of meme sharing on Twitter (now X). Focusing on the affordances of the platform such as tweets, which are the result of posting content on Twitter, quote tweets, which involve sharing other users tweet and adding commentary, and retweets, which allow the re-share of a tweet, Dynel demonstrates how these technical functions shape not only the visibility but also the interpretive potential of memes. Her analysis of retweeting as both endorsement and subtle social critique underscores the importance of listening to the silent participants but also the labour involved in meme consumption and sharing. Crucially, Dynel introduces the concept of “tacit recontextualization” (Dynel 2024: 112), whereby memes accrue new meanings through circulation among culturally literate audiences. In the context of pocket memes, Dynel’s concept of tacit recontextualization adds further nuance; it enables users to construct shared meanings around gendered clothing experiences. This perspective complicates simplistic notions of virality by revealing how meme-sharing is not just participatory but also strategically communicative, reinforcing the argument that memes operate as dynamic tools for meaning-making within broader cultural and gendered discourses.

Investigating pocket memes as expressions of the wearer’s lived experience adopts the framing of memes as forms of “networked, pictorial/caption humour and social commentary” (Mitman/Denham 2024: 1). The latter authors’ recognition of memes as both cultural labour and spectacle is particularly relevant: While pocket memes can focus social critique through the specific lens of the pocket and the gendered inequities of pocket design, they also risk dilution as they circulate widely. This tension between the impact of the meme and overexposure reveals a central paradox of meme culture: The very mechanisms that enable virality can also erode meaning. The stages of cultural arbitration and transcendence in the meme stream (cf. ibid.: 2) underscore this risk, suggesting that saturation and humour may trivialise core messages, such as those embedded in pocket memes, and therefore desensitise users through repetition and spectacle. As Mitman and Denham also explain,

“The ‘meme stream’ begins with ‘creation’, where subcultural (sometimes resistive) labour is invested in the creation of a meme… It then moves through ‘cultural arbitration’, where ‘affinity groups’ (Gee, 2005) adjudicate its value based upon often moveable reference values within the subculture” (Mitman/Denham 2024: 2).

Finally, they note, a meme reaches “transcendence, where it leaves behind most of the cultural value that it created to become allied with signifiers of profit-generating (usually small) marketing schemes or brands or to become a marketing scheme itself” (ibid.). This notion of transcendence highlights the final stage in a meme’s lifecycle, where its original critical or cultural force is co-opted for commercial ends. In the case of pocket memes, this underscores how quickly a tool for gender critique can be reframed as aesthetic content or branding device. Together, these perspectives illuminate the dynamic and often contradictory nature of meme culture, where humour and critique, visibility and trivialisation, co-exist. By focusing on the micro-context of pocket memes, this study highlights the potential for such content to prompt nuanced reflections on gendered fashion, while also acknowledging the interpretive instability that can accompany meme consumption and sharing.

The everyday is elevated via the meme. For example, the ordinary experiences of the pocket become a site of embodied cultural expression. This remediated vernacular creativity highlights the narration of “the everyday, the mundane, the in-between” (Burgess 2007: 29), and is particularly relevant for understanding the seemingly trivial yet deeply significant nature of pocket memes, which focus on an often-overlooked aspect of everyday clothing. Just as vernacular creativity captures the routine and mundane nature of daily life, pocket memes bring attention to the gendered experience of clothing, transforming these mundane issues into cultural commentary.

Pocket memes exemplify this shift, transforming a seemingly insignificant aspect of clothing into a medium for critiquing gendered norms. Milner’s concept of the memetic lingua franca reinforces this, framing memes as a universal communicative mode that allows shared meaning through visual and cultural cues (cf. Milner 2016). The apparent triviality of pocket memes, then, belies their deeper function as accessible, socially resonant critiques. However, there are also cautions against romanticising meme culture, describing it as inherently messy (cf. Bardos 2023: 191). This interpretive openness is both a strength and a vulnerability: While it enables continual reinterpretation, it also risks diluting critique and meaning through saturation or ironic detachment. In the case of pocket memes, this ambiguity is critical. Even passive engagement, such as viewing or scrolling past, contributes to the meme’s cultural footprint, enabling a form of silent participation that shapes shared understandings. These everyday interactions, active or not, are fundamental to how meme meanings are collectively negotiated and continually evolve, particularly in relation to gendered experiences of clothing.

4. Data Events and Analysis

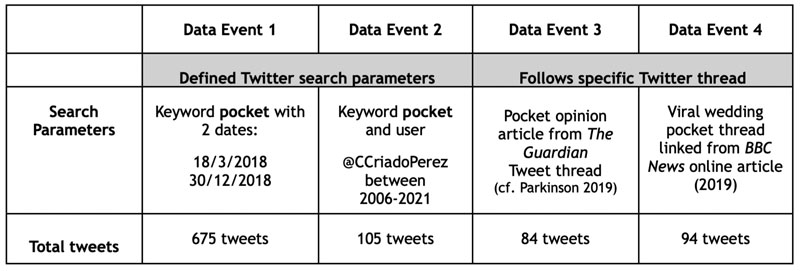

The pocket meme examples discussed in this article are drawn from a corpus compiled during my PhD research at Manchester Metropolitan University. To determine an appropriate sample size, I applied the concept of information power (Malterud et al. 2016: 1753), a qualitative research framework that prioritises data relevance over quantity. This approach enabled the selection of data that closely aligns with the research aim, capturing specific moments in time related to the gendered experience of pockets. The data set comprises four distinct data events: Two involve keyword searches for pocket combined with either specific dates or particular Twitter users; the other two focus on tracing specific Twitter threads. These are summarised in Figure 1. As introduced above, a social listening approach was adopted, which allows researchers to attend to all forms of participation in digital spaces, including those often considered passive, such as lurking or silent observation. As Adjin-Tettley and Garman note, such participants often remain invisible in traditional analyses, despite their engagement being meaningful and worthy of attention (cf. Adjin-Tettley/Garman 2023: 12).

While social listening was initially defined in the context of digital marketing, as the practice of monitoring online conversations (cf. Reid/Duffy 2018), its application here is more nuanced. Stewart and Arnold’s definition is more suitable for academic use, describing social listening as “an active process of attending to, observing, interpreting, and responding to a variety of stimuli through mediated, electronic and social channels” (Stewart/Arnold 2018: 86). In an increasingly mediated society, they suggest; “perhaps we need to recognize social listening as a means of attaining interpersonal cues and social intelligence that can empower relationships and alter the way we listen to one another through increasingly popular mediated channels.” (Stewart/Arnold 2018: 98). For brands, scraping comments from their own posts may yield consumer insights. However, valuable activity and perspectives exist beyond those immediate interactions. This case study on the pocket demonstrates how insights can be uncovered through a focused method of online observation.

The different data events illustrate how social listening, combined with information power, can generate a rich, complex understanding of user engagement, commentary, and discourse. This blended approach avoids one of the key challenges of netnographic analysis; coding and interpreting large, qualitative datasets (cf. Belk/Kozinets 2017). Here, the strength of the researcher-as-instrument is that they may perceive nuances that a data-mining algorithm may miss. This netnographic edge underscores the depth and reflexivity that human interpretation brings to social listening in digital contexts (cf. Belk et al. 2014: 273).

Fig. 1: Summary table of data events

5.Case Study Examples

The examples are presented in a narrative flow in order to demonstrate the journey of mastering pockets. This arrangement allows the pocket memes to be examined as examples of vernacular creativity. The first example shows the resourceful nature of the burdened women who do not have pockets to carry their belongings. Example two depicts the experiences of not having pockets, with empowerment and pocket posing as the final example.

Example 1: The Claw Meme

Fig. 2: The Claw meme. Originally sourced:https://x.com/strbxkei/status/1317413561136640000

The Claw meme (Fig. 2) appears in Data Event 1 and depicts two different people (that appear to be women, signified by the women’s clothing, long hair and accessories). The accompanying tweet text refers to ‘girls’, indicating that the author’s intention was to address those who wear women’s clothing. The Claw depicts the distinctive hand posture adopted by many women to carry essential items in the absence of functional pockets, which serves as a subtle yet telling symbol of gendered embodiment. This physical adaptation reflects more than a practical response; it reveals a deeper cultural script in which women are cast not as autonomous agents but as bearers of supplementary burdens. As Bari observes, “She implicitly acquiesces to this relegation, taking up a position of support or supplementation, always the accessory, never the agent” (Bari 2019: 107). In this gesture lies the quiet indignity of being socially positioned as structurally dependent, an enduring legacy of gendered expectations around labour, presence, and worth.

The responses indicate that for most, this does reflect the genuine absence of pockets in their clothing. However, reflecting the nuances of the issue, other comments share that they purposefully choose clothes that are tight fitting and without pockets, to maintain the form of the outfit. This viral meme has 10k retweets and 22k likes, which suggests that users have approved or understood the experience of the claw and have engaged in tacit recontextualisation of this pocket meme, further enhancing the significance of the meme and the consequential impact of sharing this to a further audience with the shared cultural understanding of using the claw.

Example 2: It’s Cancelled Meme

Fig. 3: It’s Cancelled Meme. Copy sourced: https://tenor.com/en-GB/view/thats-over-cancelled-gif-10367180

The It’s Cancelled meme (Fig. 3) was posted in Data Event 1, in a tweet where the author described wearing an outfit with dress and leggings to school, only to then realise the lack of pockets. The meme shows a person wearing a flamboyant fur coat, who is trying to operate a coffee machine. In the context of this example, it implies that without pockets, a day’s tasks cannot be faced. The user is unable to go about their day in comfort and practicality, which underscores how pockets allow mobility, sociability (cf. Burman/Fennetaux 2019: 143), and preparedness (see also Bari 2019). This pocket meme prompts responses that signify emotional resonance and validate the author’s experience and frustration, also appreciating the humour of the meme that indicates a dramatic, diva-like response. The comments in this thread emphasise how the seemingly insignificant issue of navigating the day without pockets is a familiar, shared experience in the contemporary community. Despite the dramatic nature of the meme, it succinctly reflects the themes of everyday frustration and disappointment within the thread, when the pocket fails the wearer with its absence.

Example 3: Vulture Pockets Meme

Fig. 4: Vulture Pockets Meme, sourced https://cheezburger.com/9631749/fourteen-oddly-specific-memes-about-pockets, vs. Wedding Pocket pose, sourced: with kind permission from oakandblossom.com

The last example takes us to the final stage of pocket mastery, where the tweet author directly shares the meme to others in a Twitter thread in Data Event 4, addressing the pleasure of posing with pockets. The tweet author tags other users to directly communicate the collective experience and emotions of posing with hands in pockets. The meme mirrors the viral image of a female wedding party in a group power pose, with hands in pockets (Fig. 4). The images of the birds are humorous because of the unexpected legs in view when the wings are splayed out, which provokes both a high arousal of humour (cf. Shifman 2014: 67) but also emotional resonance, as it makes for a compelling and arresting set of images that perfectly captures the feeling of posing with pockets. The author includes a text that directly refers to women. And the thread concurs that it is received with general comprehension of the feeling of being able to put your hands in your pockets and swish your clothing around your body, digitally conveying the potency of “our tactile relationships with clothes and the embodied experience of wearing them” (Sampson 2024: 55). The poses also evoke stances reminiscent of dominant masculine posturing, often referred to as power poses (cf. Carlson 2023). Indeed, Carlson posits that “removing the hand into clothing remains an emblem of various masculinities” (Carlson 2008: 24), reinforcing associations with traditional displays of authority and self-assurance. Such gestures are widely regarded as symbols of empowerment and confidence, which may account for the commanding presence conveyed by the bird in the images.

The here discussed Vulture meme is shared on Twitter from a linked subreddit called r/WitchesVsPatriarchy, which is a group space that has a specific set of identity markers and shared values including being a woman-centered safe space that welcomes anyone who identifies as LGBTQ+ or as an ally. While the Reddit comments are out of the scope of the dataset, this connection demonstrates the significance of the Vulture meme in a self-declared feminist space, and the shared meaning evident in a different platform, with many users in the subreddit also confirming the joy of pockets. This also highlights the potential for alternative social media platforms such as Reddit to serve as valuable sites for conducting social listening research.

6. Findings and Discussion

This section summarises the themes identified via the analysis of aboves three examples, and demonstrates how memes can contribute to the formation and strengthening of online communities. The themes also sum up how pocket memes build meaning by tapping into a shared frustration with the design of modern clothing, especially regarding gender, functionality, and societal expectations.

6.1 Identity and Empowerment

Memes often rely on shared jokes, references, or knowledge that are meaningful mainly to people with certain life experiences or those who are part of specific communities. This kind of insider understanding fosters both a sense of belonging and an implicit exclusivity among users in online spaces like Twitter. From another perspective, memes also play a significant role in reinforcing communal identities by articulating group-specific values, norms, and lived experiences. In this sense, memes function not merely as humorous content, but as cultural artefacts that facilitate social cohesion and collective self-expression within online communities.

Memes can become cultural touchstones. They act as shorthands for complex ideas or feelings that are easily understood within a group. This memetic lingua franca, which positions meme culture as a shared form of communication, transcending language barriers and fostering collective understanding among diverse audiences, makes people feel like they are part of something bigger than just a group, but rather participants of a cultural movement. The tacit recontextualisation of memes is evident in many of the comments, where simple phrases are shared, such as ‘pockets are magic’ or ‘POCKETS’, using all capital letters for emphasis. In such spaces, no further explanation is needed for an audience that has shared cultural competencies. When a community member posts a meme that taps into a collective experience, it signals a shared understanding or recognition of a certain moment or feeling. This can be particularly powerful when it relates to everyday events. Tales of unsuccessful attempts at the claw, broken phone frustrations, and lost items are told in The Claw thread, building an unspoken bond between community members.

To subsume, pocket memes can empower people, especially those who wear women’s clothing, by turning this everyday issue and frustration into a source of humour, agency, and self-expression, and allowing the users to reclaim control of the narrative. Pocket memes highlight the absurdity of the situation, which gives individuals a sense of solidarity and collective resistance. The dramatic It’s Cancelled meme shares these feelings and experiences with solidarity and understanding expressed in the respective thread. Memes can also be used to challenge the norm by suggesting that pockets are more than just an accessory: They are a basic right for all clothing wearers, regardless of their gender. Memes thus build a narrative of equality, inclusivity and fairness.

6.2 Building Shared Experiences and Memory

In sharing collective experiences or memories, memes are often used to summarise and comment on significant events or shared experiences, helping members of the community to recall and relive shared experiences. Memes often draw on shared emotions, whether it is humour, frustration, nostalgia, or joy. When memes reflect a collective emotional experience, they foster a sense of solidarity. For instance, memes about frustration with clothing, and the gender inequality of pockets create emotional resonance (cf. ∆ 2023: 245) with the audience because they tap into common struggles, experiences and emotions. This emotional resonance also occurs as positive emotions, or high arousal emotions (cf. ∆ 2014: 67), for example, the joy and celebration of pockets and posing. The shared experience is the driver for the sharing and tacit recontextualization in all examples.

6.3 Gender and Inequality

Gender disparity in pocket accessibility is evident in pocket memes, which critique the persistent inequality in fashion design, particularly the industry’s longstanding tendency to prioritise aesthetics over functionality in women’s clothing (cf. Carlson 2023). These memes highlight how women’s fashion often neglects practicality, subtly reinforcing broader societal expectations that women rely on external accessories such as bags or purses. Through humour, pocket memes expose and challenge gendered assumptions embedded in design, illustrating how the fashion industry frequently fails to meet basic functional needs despite presenting itself as responsive to consumer demand. This critique parallels findings on unisex clothing, which reveal a disconnect between designers, who tend to focus on the social context of fashion, and consumers, who prioritise style and wearability (cf. Bardey/Achumba-Wöllenstein/Chiu 2020: 436). Furthermore, pocket memes expose the traditionally binary and rigid structure of the fashion industry. However, there is a growing consumer interest in unisex, androgynous, and gender-neutral clothing styles that challenge these binary norms, provoking a visible response from the fashion industry in its increasing offerings of unisex and gender-neutral garments (cf. Reilly/Barry 2020: 7). Pocket memes, therefore, not only expose persistent gendered limitations in clothing design, but also sit within a broader cultural moment in which both consumers and designers are beginning to question and reshape the binary structures that have long defined fashion.

6.4 Participation and Co-creation

Users and communities do not just consume memes; they create, remix, and spread them. The visual absence of pockets from all the meme examples demonstrates how the meaning is alternatively imparted via a common repertoire of references that exists with the online community. This tacit recontextualization (cf. Dynel 2024: 112) strengthens the bonds within a given group, which not only spreads the meme but also encourages members to engage actively in the group’s conversations. This is evident when the Vulture meme is shared between Twitter and Reddit platforms and prompts a subreddit discussion thread about gendered pockets. In this instance, the meme seems to provide a low-risk way of expressing complex or sensitive experiences around gender and gender identity in a safe space, one that offers some protection from the trolling or cyberbullying often fuelled by homophobia, transphobia, or gender-based discrimination.

7. Conclusion

The pocket, often overlooked as a mundane element of clothing design, carries a deep history of gendered significance. As outlined in the introduction, the inclusion or omission of functional pockets in women’s clothing has long mirrored broader societal inequalities in autonomy, mobility, and access to resources. This study contributes to the limited body of work on contemporary pockets by shifting the lens toward wearer perspectives and digital discourse, demonstrating how these symbolic tensions persist and evolve in online spaces. Memes, as explored throughout this paper, serve as vital instruments of participatory culture. They encapsulate collective emotions and everyday experiences through humour, repetition, and intertextual reference. Pocket memes reveal how users interpret and critique the ongoing gender disparities in clothing design. Even when visually, a pocket is absent, as in the meme case studies, the cultural message of pockets embedded in the memes is still evident. This underscores their power as means for shared understanding and social commentary, reinforcing Mitman and Denham’s framing of memes as “collective, networked, pictorial, and caption humour and social commentary” (Mitman/Denham 2024: 1).

The social listening methodology adopted in this study, guided by Malterud et al.’s framework of information power and Partington’s interpretation of intertextuality, enables a focused yet rich examination of the data. Rather than seeking data saturation, this approach attends to the ways in which meaning is co-created by users through both active expression and quieter forms of engagement. The analysis of defined data events on Twitter mirrors how content is encountered in real time and enables insights into how users forge intertextual relationships between digital content and embodied experiences.

The three pocket meme case studies illustrate how the pocket, as a design feature, functions symbolically within contemporary digital culture. It becomes a site of frustration, humour, critique, and solidarity. Memes about pockets do not merely highlight the absence of fabric. They foreground systemic inequities and mobilise online users around a shared point of cultural tension. In this context, the meme operates as both cultural artefact and discursive tool, shaping how everyday objects are understood within gendered frameworks.

In summary, the findings of this study illustrate how seemingly trivial aspects of fashion, like the pocket, carry cultural significance and provoke meaningful online engagement. Memes transform these objects into powerful symbols of gender politics and collective identity. This research combines historical context, a social listening approach to data collection via social media, and thematic analysis. In following the pocket from a personal necessity to a site of cultural meaning this research affirms the pocket’s continuing role as a material and symbolic space where contemporary gendered experiences are negotiated, resisted, and reimagined. For me, pockets have become a non-negotiable feature when choosing and wearing clothes.

Literature

Adjin-Tettley, Theodora D.: Garman, Anthea: Lurking as a mode of listening in social media: motivations-based typologies. In: Digital Transformation and Society 2 (1), 2023, pp. 11–26. https://doi.org/10.1108/DTS-07-2022-0028 (23.03.2025)

Bardos, Bence: Frogs and Ogres: Transformation, Reuse and Creativity in Meme Culture. PhD Thesis. University of Kent, 2023 (23.03.2025)

Bari Shahida K: Dressed: the secret life of clothes. London [Jonathan Cape] 2019

Belk Russell; Kozinets Robert: Videography and Netnography. In: Kubacki Krysztog; Rundle-Thiele Sharyn (ed.): Formative research in social marketing: innovative methods to gain consumer insights. Singapore [Springer] 2017, pp. 265–281

Burgess Jean: Vernacular Creativity and New Media. PhD thesis. Queensland University of Technology. 2007. https://eprints.qut.edu.au/16378/ (23.03.2025)

Bardey, Aurore; Achumba-Wöllenstein Judith; Chiu, Pak: Exploring the Third Gender in Fashion: From Consumers’ Behavior to Designers’ Approach towards Unisex Clothing. In: Fashion Practice 12, (3) 2020, p. 421–439

Burman Barbara: Pocketing the Difference: Gender and Pockets in Nineteenth Century Britain. In: Gender and History 14 (3), 2002, p. 447–469

Burman Barbara; Fennetaux Arianne: The Pocket: A Hidden History of Women’s Lives 1660–1900. London [Yale University Press] 2019

Carlson Hannah: Idle Hands and Empty Pockets: Postures of Leisure, Stella Blum Grant Report. In: Dress 35, 2008, pp. 7–27

Carlson Hannah: Pockets: An Intimate History of How We Keep Things Close. New York [Hachette] 2023

Crawford Kate: Listening, not Lurking: The Neglected Form of Participation (2011). In: Grief Ajo; Hjorth Larissa; Lasén Amparo (ed.): Cultures of Participation. Berlin [Peter Lang] 2011, pp. 63–77

Crawford Kate: Following you: Disciplines of listening in social media. In: Continuum 23 (4), 2009, pp. 525–535. https://doi.org/10.1080/10304310903003270 (23.03.2025)

Dawkins Richard: The Selfish Gene (30th anniversary ed.). Oxford [Oxford University Press] 2006

Diehm Jan; Thomas Amber: Women’s Pockets are Inferior. In: The Pudding.com. 2018. https://pudding.cool/2018/08/pockets/ (23.03.2025)

Dior Christian: The little dictionary of fashion: a guide to dress sense for every woman. London [V&A] 2007

Dynel Martha: The pragmatics of sharing memes on Twitter. In: Journal of Pragmatics 220, 2024 pp. 110–115. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0378216623002989 (23.03.2025)

Fitch Samantha: The Gendered Pocket: Fashion and Patriarchal Anxieties about the Female Consumer in Select Victorian Literature. [University of Pennsylvania, PhD Thesis] 2017. https://pqdtopen.proquest.com/doc/1950503366.html?FMT=ABS (23.03.2025)

Gorea Adriana; Roelse Katya; Hall Martha: The Book of Pockets. London [Bloomsbury]

Hvass Holm C: What Do You Meme? The Sociolinguistic Potential of Internet Memes. In: Leviathan Interdisciplinary Journal in English 7, 2021, pp. 1–20

Iloh Constance: Do It for the Culture: The Case for Memes in Qualitative Research. In: International Journal of Qualitative Methods 20, 2021, pp. 1–10

Johnson Paul: The Power of a pocket; why it matters who wears the trousers. In: The Spectator, 04/06/2011. https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/the-power-of-a-pocket/ (23.03.2025)

Kozinets Robert; Dolbec Pierre-Yann; Earley Amanda: Netnographic analysis: Understanding culture through social media data. In: Flick, Uwe (ed.): The SAGE handbook of qualitative data analysis. London [Sage Publications] 2014, pp. 262–276

Malterud Kirsti; Siersma Vilkert Dirk; Guassira Ann Dorit: Sample size in qualitative interview studies: Guided by information power. In: Qualitative Health Research 26 (13), 2016, pp. 1753–1760. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732315617444 (23.03.2025)

Matthews Christopher Todd: Form and Deformity: The Trouble with Victorian Pockets. In: Victorian Studies 52 (4), 2010, pp. 561–590

Milner Ryan M: The world made meme : public conversations and participatory media. Cambridge, Massachusetts [The MIT Press] 2016

Mitman Tyson; Denham Jack: Into the meme stream: The value and spectacle of Internet memes. In: New Media and Society 0, 2024, pp. 1–17

Myers Janet C: Picking the New Woman‘s Pockets. In: Nineteenth-Century Gender Studies 10 (1), 2014, p. 29

Parkinson Hannah J: I love a pocket – except the fake ones. I mean, who invented that charade? In: The Guardian, 20/12/2019. https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2019/dec/20/i-love-a-pocket- except-the-fake-ones-i-mean-who-invented-that-charade (23.03.2025)

Partington Angela: Class, clothes, and co-creativity. In: Clothing Cultures 1, (1), 2013, pp. 7–21

Reilly Andrew Hinchcliffe; Barry Ben (ed.): Crossing gender boundaries : fashion to create, disrupt and transcend. Bristol, UK [Intellect] 2020

Roach-Higgins Mary Ellen; Eicher Joanne B: Dress and Identity. In: Clothing and Textiles Research Journal 10, (4), 2002, pp. 1–8

Sampson Ellen: Pockets of Affect/Containers of Feeling (2024). In: Brown James; Jamieson Anna; Segal Naomi (ed.): The Cultural Construction of Hidden Spaces : Essays on Pockets, Pouches and Secret Drawers. Boston [BRILL] 2024, pp. 52–65

Stewart Margaret c.; Arnold Christa L.: Defining Social Listening: Recognizing an Emerging Dimension of Listening. In: International Journal of Listening 32 (2), 2018, pp. 85–100 https://doi.org/10.1080/10904018.2017.1330656 (23.03.2025)

Shifman Limor: Memes in Digital Culture. Cambridge, MA [The MIT Press] 2014

Skov Lise; Riegels-Melchoir Marie: Research Approaches to the Study of Dress and Fashion. In: Creative Encounters Working Papers 19, 2008

Talcott Samuel: The Secreted Self. In: Brown, James; Jamieson, Anna; Segal, Naomi (eds.): The Cultural Construction of Hidden Spaces : Essays on Pockets, Pouches and Secret Drawers. Boston [BRILL] 2024, pp. 197–210

Wilson Elizabeth; Taylor Lou; BBC: Through the looking glass : a history of dress from 1860 to the present day. London [BBC Books] 1989

Biography

Ruth Eaton is a Lecturer in Contextual Studies and a doctoral researcher in fashion and media studies at Manchester Metropolitan University. Her PhD examines the pocket as a site of social and cultural meaning, drawing on digital ethnography and analysis of Twitter narratives. Her research engages with everyday dress practices, material culture, and participatory online communities. Ruth’s work has been featured in The Guardian and reflects an interdisciplinary approach grounded in both academic inquiry and professional practice. Prior to entering academia, she held senior roles in the fashion retail sector, including brand development, project management, and employee relations.

About this article

Copyright

This article is distributed under Creative Commons Atrribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0). You are free to share and redistribute the material in any medium or format. The licensor cannot revoke these freedoms as long as you follow the license terms. You must however give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. You may not apply legal terms or technological measures that legally restrict others from doing anything the license permits. More Information under https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.en.

Citation

Ruth Eaton: Pocket Memes and the Gendered Pocket: A Social Listening Approach to Intertextuality on Twitter. In: IMAGE. Zeitschrift für interdisziplinäre Bildwissenschaft, Band 42, 8. Jg., (2)2025, S. 190-208

ISSN

1614-0885

DOI

10.1453/1614-0885-2-2025-16667

First published online

September/2025