By Gwyneth Holland

Abstract

This paper considers how theories of the posthuman can help to understand the connection between physically and virtually dressed bodies. Virtual fashion is a layered image: pixels of a 3D garment are placed over pixels of a photographed or digitally rendered body. Within those layers are experiences of body image, identity and experimentation, interleaved with technical restrictions and exclusionary fashion practices. The paper underlines the need for representation and expression across worlds, which can create challenges for existing body norms. Situated within fashion and fat studies, I particularly focus on the nascent areas of fat and fashion futures, which enable a greater consideration of the impacts of current practices on aspiration and opportunity. Virtual worlds can represent different identities and representations, but they are not free from the structures that affect bodies in physical realms (Ma 2024), meaning that the exclusion of fat bodies in physical fashion is replicated in virtual fashion. However, Braidotti’s (2013) and Haraway’s (2016) discussions of technical-human hybridity suggest potential for this sector to destabilise body hierarchies by blurring the lines between physical, digital, real and fantasy.

For the present analysis, it is useful to distinguish between ‘digital’ and ‘virtual’ fashion, though the terms are often used interchangeably (Boughlala/Smelik 2024). Digital fashion (DF) combines a wide range of technologies which enable the visualisation, experience and commerce of physical garments. Virtual fashion (VF), on the other hand, refers to three-dimensional graphic renderings of garments which may be superimposed on photos or videos of bodies, or as cosmetic effects for online avatars, such as gaming and metaverse characters (ibid.). This paper focuses on the latter phenomenon as it is applied especially to fashion images and digital avatars.

Dieser Beitrag erörtert, wie Theorien des Posthumanen dazu beitragen können, die Verbindung zwischen physisch und virtuell bekleideten Körpern zu verstehen. Bei virtueller Mode handelt es sich um ein geschichtetes Bild: Pixel eines 3D-Kleidungsstücks werden über Pixel eines fotografierten oder digital gerenderten Körpers gelegt. Innerhalb dieser Schichten reagieren Erfahrungen von Körperbild, Identität und Erkundung mit technischen Einschränkungen und exkludierenden Modepraktiken. Der vorliegende Text unterstreicht die Notwendigkeit der Darstellung und des Ausdrucks in verschiedenen Welten, was eine Herausforderung für bestehende Körpernormen darstellen kann. In den Fashion und Fat Studies situiert, konzentriere ich mich besonders auf deren im Entstehen begriffenen Zukünfte, was eine vertiefende Befassung mit den Auswirkungen aktueller Praktiken auf Bestrebungen und Möglichkeiten zulässt. Virtuelle Welten können andere Identitäten und Repräsentationen ermöglichen. Dennoch sind sie nicht frei von den Strukturen, die Körper in der physischen Welt betreffen (Ma 2024). Das hat u.a. zur Folge, dass der Ausschluss von dicken Körpern in der physischen Mode in der virtuellen Mode repliziert wird. Braidotti’s (2013) und Haraway’s (2016) Diskussionen über technisch-humane Hybridität deuten jedoch darauf hin, dass dieser Sektor das Potenzial hat, Körperhierarchien zu destabilisieren, indem er die Grenzen zwischen Physischem, Digitalem, Realem und Phantastischem verschwimmen lässt.

Obgleich die Begriffe oft synonym verwendet werden (Boughlala/Smelik 2024) ist es für die hier geschehene Analyse sinnvoll, zwischen ‚digitaler‘ und ‚virtueller‘ Mode zu unterscheiden. Digitale Mode (digital fashion, DF) umfasst eine breite Palette von Technologien, die die Visualisierung, das Erleben und den Handel mit physischen Kleidungsstücken ermöglichen. Virtuelle Mode (virtual fashion, VF) hingegen bezieht sich auf dreidimensionale grafische Darstellungen von Kleidungsstücken, die auf Fotos oder Videos von Körpern gelegt oder als kosmetische Effekte für Online-Avatare, wie z. B. Spiel- und Metaverse-Charaktere, eingeblendet werden können (ibid.). Dieser Beitrag konzentriert sich auf das letztgenannte Phänomen, insbesondere wie es im Fall von Modebildern und digitalen Avataren angewandt wird.

Fig. 1: DressX designs for the Covet Fashion game, 2025, featuring garments worn on physical and virtual bodies

Introduction

This paper considers virtually dressed bodies as an extension of physical bodies—not just digital dolls to be played with, but a key part of users’ own identities and body image (cf. Park/Ogle 2021). In an expansion of his theory of the extended self, Russell Belk suggests that virtual avatars become part of their users’ identities. As users begin to design, dress, name and control avatars, “we gradually not only become re-embodied but increasingly identify as our avatar” (Belk 2013: 481). Wearing garments chosen by the user, in a form chosen by the user, giving a particular look or powers to the user (Boughlala/Smelik 2024), avatars may be considered dressed extended selves, functioning “as both a private embodiment and a public representation within virtual worlds” (Ma 2024: 2).

Haraway (2016) and Braidotti (2013), in particular, have argued for such an expansive understanding of the body, to include non-human aspects such as technology, as a way to de-essentialise female bodies and offer broader possibilities for identity and gender. With digital selves becoming part of an extended idea of self, we may consider virtual fashion to contribute towards cyborg identities, as conceptualised by Donna Haraway. In The Cyborg Manifesto, Donna Haraway (2016: 14) proposes the cyborg form as one which can challenge body ideals and stigmas through “transgressed boundaries, potent fusions, and dangerous possibilities”. The virtual dressed body could become a key part of a more inclusive future, offering new visions of design, embodiment and self-presentation.

Anneke Smelik (2021) has described a posthuman turn in fashion, as designers, practices and aesthetics blend the organic and the technical in more seamless ways. Smelik defines the posthuman as “a hybrid figure who decenters human subjectivity, celebrating in-between-ness, by making alliances with all kinds of non-humans” (2021: 58). In the case of virtual fashion, this reflects the alliance between the physical and virtual body and its ways of dressing. Drawing on Deleuze and Guattari, Currier goes further, to consider bodies as an assemblage of organic and technical elements, which may shift and flow to produce “transitory but functional assemblages” (Currier 2003: 326). Deleuze and Guattari argue that the component parts of an assemblage are not unified, but a flow of components that meet and shift to create a whole. This conceptualisation allows for the shifting approach to technical engagement shown in contemporary culture, and fashion consumption. Humans no longer see themselves as online or offline beings but always connected physical-digital subjects, creating different formations according to space, circumstance and discourse (Currier 2003). As such, the body is always in a state of becoming (Smelik 2021), creating challenges to existing categories and offering different horizons for fat bodies (Grosz 1993).

Fat studies emerged as an academic field in the 90s, partly due to cultural studies’ turn to the body (Wykes 2014), and while the academy reflects a growing understanding of the relationship between fat bodies and clothing, this largely focuses on histories and worn experiences (Volonte 2021; Peters 2023). There is great potential to consider fat bodies within the future of fashion, as Ben Barry (2021) and others have explored. The fashion industry, as a whole, has long sidelined and othered fat bodies (Peters 2023), but without the tangible characteristics of seam placement and fabric costs that delineate physical fashion, virtual fashion can offer limitless fantasies and experimentation to fat bodies (Yingling 2016), especially vital when this may be unavailable in physical fashion.

Futurity is a key consideration in virtual fashion, as so many of the brands are framed as the ‘future of fashion’ in both the academy and fashion media (English/Munroe 2022; Abad 2020). Futures also play an important role in fat studies, as explored recently by Puig and Schlauderaff (2021), who advocate for a fluid approach to discussions of fat futures, as a way to trouble boundaries between disciplines, as well as understandings of the body, which has informed this work.

1. Potential and bias

The fashion system has become increasingly digital in the last decade (Boughlala/Smelik 2024; English/Munroe 2022: 229), as more fashion experiences are mediated through the smartphone or laptop screen, designed on 3D platforms, bought and sold through e-commerce, or inspired by social media posts and influencers. As a result, bodies are increasingly negotiated through the smartphone screen or camera’s eye, demonstrating “the female body’s heavily mediated, hybrid materiality in a digital age” (Greene 2021: 309). Filtered and edited, social media bodies become virtual avatars, designed for the approval of each app and its algorithm.

Virtual fashion is largely designed for this digital gaze, as virtual fashion platform DressX states in its guidance to contributors that users will wear the garments “to ‘go out’ to social media – they will post it on Instagram first of all. That’s why it should naturally match the visual language of the platform” (Dressx, 2025). It is apposite that virtual fashion brands are designing towards this platform, incorporating its potentialities and biases in each design. Social media such as Instagram are a key battleground for body images, as a contributing factor to ideals of body perfection, as well as a venue for body positivity and fat activism movements (Bala 2021; Mccomb/Mills 2022).

Virtual fashion may be little more than a sophisticated image filter, but users’ relationships between these garments and their embodied selves can be much more profound. Denegri-Knott and Molesworth (2010) suggest that virtual consumption fulfils four functions: to stimulate consumer desire; actualise possible daydreams; actualise impossible fantasies; and facilitate experimentation. Some brands, such as H&M, Hanifa or Balenciaga, have used virtual fashion shows, Snapchat filters and gaming platforms to stimulate the desire to shop (Boughlala/Smelik 2024). For this paper, I will focus on VF’s ability to help people experiment with fantastical or realistic versions of themselves in online worlds (Ma 2024).

Just as definitions of dress include the body (Eicher 1995), discussions of virtual fashion must consider the body. Fashion is explored as an embodied practice by Joanne Entwistle (2015) and others, but the relationship between individuals and their avatars suggests a posthuman idea of embodiment, which incorporates elements of physical and virtual identity. For Ma (2024), “virtual dress” incorporates the virtual body and its modifications, including facial features, body silhouettes, skin, hair, and virtual clothing. As computer-generated layers, virtual bodies and virtual dress co-constitute each other, thus the garments design the body, shaping ideals and visions of future bodies (Fry 2020).

KatherinE Hayles has suggested that online, “the overlay between the enacted and the represented bodies is no longer a natural inevitability but a contingent production” (1999: xiii), where the visualisation of the body in digital imagery co-creates physical identity: a cyborg identity that blurs the line between physical characteristics and capabilities, and the fantastical powers and appearances of online worlds. Scholars including Anne Balsamo (1996) and Donna Haraway (2016) argue that such cyborg bodies can offer an important challenge to dominant narratives and gendered ideals, a challenge which virtual fashion brands often echo, as explored below. If virtual fashion is to be a site of resistance, it must support and enable a wider range of identities, to which all bodies may aspire (Grosz 1994). Virtually dressed cyborg bodies, with their almost limitless boundaries, can be more real, more strange, more diverse, challenging the hegemony of idealised fashion forms and presenting different ways of thinking about the body and its beauty.

2. Futuring fashion

Virtual fashion brands express a desire to create a new, different form for fashion, one which is queer-inclusive, body-diverse, fantastical, affordable and sustainable (Bernat 2024). Bodies seen in futuristic fashion imagery may be seen and celebrated as bodies of the future, not those awaiting remedy, such as weight loss or medical intervention (Lebesco/Braziel 2001; Wykes 2014). Instead, these bodies might offer what Anna M. Puhakka (2025) describes as “preferable fat futures”, a view on what the future could be, one in which fat bodies are welcomed in fashion and beyond. By offering new and different representations of the body, virtual fashion can offer a future that enables fat cyborgs to express the fullness of their identities and explore their fantasies.

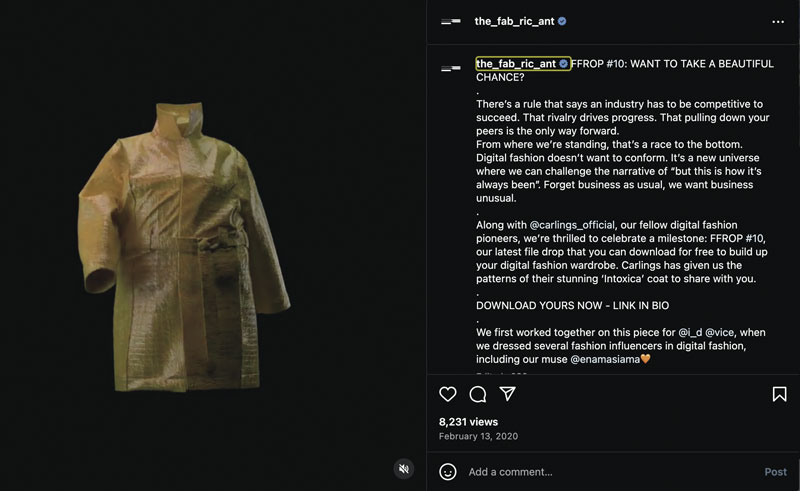

A collaboration between virtual fashion company The Fabricant and model and influencer Enam Asiama is one of few diverse bodies featured by the brand. Asiama is an advocate for plus-size representation and a self-described “FatQueerFemme”. An Instagram post from the brand, dated February 13, 2020, features an invisible figure based on Asiama’s body shape wearing a yellow mid-length crocodile-effect coat. Though the head, legs and hands of the virtual body are not visible, her larger body is evident in the proportions and fit of the yellow coat. The inclusion of Asiama’s body type in this early image from The Fabricant, in conjunction with messages of nonconformity and difference in the caption suggest that the company intends to challenge some of the inequities and issues created by the existing fashion system, including sizeism.

Fig. 2: Screenshot of The Fabricant Instagram account dated February 13, 2020, featuring a virtual model of influencer Enama Siama

The Instagram caption suggests a progressive approach, eschewing the capitalist ideals of competition and success to create new horizons for fashion, ones which include fat bodies. An extract from the caption is shown below:

Digital fashion doesn’t want to conform. It’s a new universe where we can challenge the narrative of ‘but this is how it’s always been’. Forget business as usual, we want business unusual (…) We first worked together on this piece for @i_d @vice, when we dressed several fashion influencers in digital fashion, including our muse @enamasiama

The new fashion system proposed here by The Fabricant offers a clean slate for fat people (and the wider fashion industry), and a challenge to its systemic body chauvinism and exclusion of differentiated bodies (Bernat 2024). However, it should be noted that, despite describing Asiama as The Fabricant’s ‘muse’, she has not been featured again by the brand, and its claims to disrupt ‘business as usual’ have yielded limited results for body inclusivity. Only five of the hundreds of posts featured on The Fabricant’s Instagram account, between its first post on January 15 2018 and the most recent post at time of going to press, dated March 25 2025, include fat bodies. Discussing virtual bodies, Brachtendorf (2022) comments that “appearance and personality are planned and produced centered on the market”. The brand is thus holding true to virtual fashion brands’ call to design for social media platforms, and thereby succumbing to its restrictive visual standards.

As a utopian vision of fashion, the ability of different bodies to wear VF is important, so that the future is available to all. Elizabeth Grosz (1999) argues that futures require a conceptual horizon within the unpredictable and unexpected, and the inclusion of Asiama’s body in an early post by The Fabricant suggests a desire to offer a new approach to fashioned bodies. These are themes emphasised by the Institute of Digital Fashion (a consultancy which advocates for better practices in virtual fashion), whose research shows that virtual customers expect diversity to be pushed further, to include different gender representations, body weights, genitalia, limb differences and disability aids (2021).

3. My avatar, myself

As the fashion industry retreats from representing bigger bodies on catwalks, and in fashion imagery (Shoaib 2025), there is a dearth of inspiration for fat people to see themselves in a fashionable future, a space that virtual fashion is well-positioned to fill. The ability to play with fashion, to try on different styles, colours and silhouettes, is vital to the formation and expression of identity (Roach-Higgins/Eicher 1992; Volonte 2021). As the avatar is the primary way that users may interact with others online, it serves an important role in self-presentation (Boughlala/Smelik 2024: 4), creating a hybrid habitus that blends physical being with virtual becoming (Ma 2024). This is supported by research into users of virtual worlds and gaming platforms, suggesting that users buy avatar outfits for similar reasons to physical fashion purchases: to demonstrate communal identity, to express their identity or to dress up for fun (Hembree/Hodges 2020; Young/Taylor 2021). Virtual fashion offers the ability to experiment further, with diaphanous, mobile and shape-shifting garments that cannot be replicated offline. These bodies, freed from many physical and societal restrictions, are able to create new assemblages of identity, offering greater possibilities for embodiment and dress.

Virtual fashion brand Tribute has attempted to situate its clothing in a wider range of identities, via a collaboration with Paper Magazine and LGBTQIA+ model agency New Pandemics (Abad 2020). A fashion shoot published online in June 2020 shows not just fantastical fashion (including liquid metallic finishes, expandable dresses and floating fabrics) but more fluid ideas of what fashioned bodies can be: diverse, non-binary and even fat. Model Mycky, a fat woman, is one of three models featured in the shoot. She wears two different virtual garments, the first is a chromium yellow metallic gown, with a bodice that moulds around her curves before flaring out to a full skirt. At the back, a giant bow has a puffy, inflated appearance. The garment evokes metallic party balloons, joyfully enabling Mycky to take up space. The second look is a semi-sheer pair of cropped trousers with an iridescent fish-scale appearance and a red tint, which she pairs with chunky boots and a ruched bikini top. Here, rounded flesh, sheer layers and ethereal textures are assembled together, creating “new modes and practices of embodiment which express difference rather than sameness” (Currier 2003: 323).

The photographs show Mycky effortlessly embodying these virtual garments, defining not just their form, but how they are seen, her assemblage of technicality and physicality creating novel aesthetics for futuristic fashion. Oversized, shiny and otherworldly, her cyborg body shows the potential for virtual fashion to promote fat futurity, using digital tools to foster self-actualisation for fat people, and enabling them to celebrate their body as a current and futuristic entity (Seely 2012).

4. Fat futures

Framing virtually dressed bodies as an assemblage or cyborgs raises interesting contradictions. While Haraway may offer the cyborg as an agent of change, many popular visualisations of cyborg bodies maintain fashionable norms. In film, television and fashion imagery, cyborg bodies are usually athletic and model-thin, depicting a limited ideal of as physical perfection. Fat bodies are rarely represented in such visions of the future. In the futuristic book and film series Dune, the only larger body represented is Baron Harkonnen, an evil grotesque (Earle 2024), while the world of Pixar film Wall-E frames fat as a dystopian future, “modernity gone awry” (Ward 2013) shown through its immobile, overstimulated, unhealthy consumers. These representations reflect a future in which all bodies are slim, healthy, youthful and beautiful: a westernised, patriarchal, classed idea of perfection.

A body is expected to be flawless. This is evident not only in how society is built to favour the able-bodied, the thin, and the attractive, but also in the imagery that is produced about our potential futures (Earle 2024: 4).

The lithe and lean cyborg forms of the future, like virtual influencers, avatars and other virtual bodies (Shin/Lee 2023), are presented as the apotheosis of form and function, an ideal to which all should aspire, while fat bodies are a symbol of dystopian disrepair, one which will not reach its “desirable potentiality” of thinness (Yingling 2016: 28).

Fat futures can only be fulfilled inasmuch as virtual bodies and virtual fashion can offer a true extension, or assemblage, of the physical body with its virtual selves. As Tosha Yingling states, “Fat is flesh, reduced to its contours, but cyberspace has no linearity and digitisation has no physical space” (2016: 37). Boughlala and Smelik posit that videogame practices and technologies have informed much of the development of virtual fashion (2024: 53), as the sector already has established modes of designing and representing bodies in digital formats. Employing design engines, 3D models and creative skills from gaming, virtual fashion also replicates some of its aesthetics, meaning that there are limits to the degree of self-identification, due to the narrow range of body types offered by games and metaverse platforms (Meadows 2008; Park 2018; Young/Taylor 2021). Sizing options for avatar design are often simplistic controls that simply stretch the body wider, rather than creating realistic fat bodies. While it is possible to create taller or more muscular avatar shapes, few games offer the option to create fat or plus-size avatars (Harper 2019).

Options for realistic body representations are hampered by software, and the skills of its operators, to create anything but the most generic human-style forms. Digital fashion design platform Clo3D offers standard slim mannequin shapes on which to design virtual (and physical) fashion, while the Metahuman modelling programme, used by virtual fashion house The Fabricant (as well as many videogame developers) includes eighteen generic body types, variations of short/average/tall and thin/average/fat. 3D designers may make adjustments to the standard templates, to represent more realistic or nuanced bodies, but many virtual fashion designers come from a traditional fashion background, and are feeding their knowledge and its systemic body size biases into the software (Särmäkari 2020; Seely 2012), thus creating a future based on existing restrictions. Critical futurist Ziauddin Sardar (2010) writes that, “Forecasts and visions are themselves epistemological activities” which “do not yield knowledge of the future itself” but “provide us with manufactured knowledge of a restricted number of possibilities”. The reliance on standardised, and idealised, slim templates, limit the possibilities for any fat, or fashion, future. Fat bodies are thus regulated by the systems designed to create virtual clothing, maintaining their differentiation from a futuristic ideal (Jones 2014).

The ability to design for bodies unlimited by physical space requires not just greater skill, but a more open horizon, to consider what future bodies can be, and how they might appear. The replication of idealised future bodies—slim, muscular, perfect—leaves few inspirations for multiplicity. In this way, virtual fashion offers as many opportunities as limitations.

5. Conclusion

Considering virtual fashion through the lens of feminist posthumanism allows a critical understanding of the potentialities and restrictions operating within this nascent sector. Blended with thinking on fat and fashion futures, these examples demonstrate the importance of considering the impact of futuristic technologies, and the ways that they may limit or liberate different bodies.

The brands operating in virtual fashion thus far show glimpses of multiplicity, but operating within the ideals and practices of the traditional fashion industry, such as Instagram images or standardised design templates, they replicate existing ideas. As Elizabeth Grosz (1999: 19) proposes “difference is crucial to opening up an indeterminate future in which the new might appear”. Where virtual fashion brands work with fat bodies, such as Tribute’s collaboration with New Pandemics, they not only exemplify posthuman fashion, but highlight new horizons for fat bodies.

There is still much work to do: The extant restrictions created by the fashion industry do not need to be part of its future, but this requires a disassembly of standards in design and representation, including the platforms on which virtual bodies and fashion are designed, the social media platforms on which they are displayed and the metaverse environments where they are embodied. As long as virtual fashion brands are able to continue operating beyond the traditional fashion system, they show potential to offer a different future that enables fat bodies to be future bodies.

Literature

Abad, Mario: Tribute Brand Is Making ‚Contactless‘ Clothes for the Cyber Age. PaperMag, 2020. https://www.papermag.com/tribute-brand-digital-clothing-interview#rebelltitem3

Bala, Divya: How TikTok Put Mid-Size at the Frontier of Inclusivity. Vogue, 2021. https://www.vogue.co.uk/beauty/article/mid-size-body-inclusivity

Balsamo, Anne: Technologies of the Gendered Body: Reading Cyborg Women. Durham [Duke University Press] 1996

Belk, RusseLl W: Extended Self in a Digital World. In: Journal of Consumer Research, Volume 40, Issue 3, 2013, pp. 477–500

Bernat, Sara Emilia: Is Digital Fashion Socially Equitable? In: SPICHER, MICHAEL R.; BERNAT, SARA EMILIA; DOMOSZLAI-LANTNER, DORIS (ed.): Digital Fashion: Theory, practice, Implications. London [Bloomsbury Visual Arts] 2024

Brachtendorf, Charlotte: Lil Miquela in the folds of fashion: (Ad-)dressing virtual influencers. In: Fashion, Style & Popular Culture, 9:4, 2022, pp. 483–499

Braidotti, Rosi: The Posthuman. Cambridge [Polity Press] 2013a

Braidotti, Rosi: Posthuman Humanities. In: European Educational Research Journal, 12:1, 2013b

Bye, Elizabeth; Labat, Karen; Mckinney, Ellen; Kim, Dong-Eun: Optimized pattern grading. In: International Journal of Clothing Science and Technology, 20, 2008, pp. 79–92

Christel, Deborah A. And Williams, Susan C.: What plus-size means for plus-size women: A mixed-methods approach. In: Studies in Communication Sciences,18:2, 2018

Currier, Dianne: Feminist technological futures: Deleuze and body/technology assemblages. In: Feminist Theory, 4:3, 2003, pp. 321–338

Denegri-Knott, Janice And Molesworth, Mike: Concepts and practices of digital virtual consumption. In: Consumption Markets & Culture, 13(2), 2010, pp. 109–132

Dressx: Check List for 3D designers requirements. DressX, 2025. https://docs.google.com/document/d/1mKyVJge5xt3fMzbjYUZ8ggiQ6av6-F0Nt04pj7UUTKk/edit?usp=sharing

Earle, Joshua: The Problem of the Sexy Cyborg: the aesthetics and tropes of cyborg imagery. In: Journal of Ethics and Emerging Technologies, 34:1, 2024

Eicher, Joanne B.: Dress and Ethnicity: Change Across Space and Time. Ethnicity and Identity. Oxford [Berg] 1995

English, Bonnie. And Munroe, Nazanin: A Cultural History of Western Fashion: From Haute Couture to Virtual Couture. 1st edn. London [Bloomsbury Visual Arts] 2022

Entwistle, Joanne: The fashioned body : fashion, dress, and modern social theory. Second edition. Cambridge [Polity Press] 2015

Fry, Tony: Design Futuring: Sustainability, Ethics and New Practice. London [Bloomsbury Visual Arts] 2009

Greene, Amanda K.: Flaws in the highlight real: fitstagram diptychs and the enactment of cyborg embodiment. In: Feminist Theory, 22 :3, 2021, pp. 307–337

Grosz, Elizabeth: Volatile Bodies. Sydney [Taylor & Francis Group] 1994

Grosz, Elizabeth: Becomings. Explorations in Time, Memory, and Futures. Ithaca, NY [Cornell University Press] 1999

Haraway, Donna. J: The Cyborg Manifesto. In: Manifestly Haraway. Minneapolis [University of Minnesota Press] 2016

Harper, Todd: Endowed by Their Creator: Digital Games, Avatar Creation, and Fat Bodies. In: Fat Studies, 9:3, 2019. pp. 259–280

Hayles, N. Katherine: How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies In: Cybernetics, Literature, and Informatics. Chicago, Ill. [The University of Chicago Press] 1999

Hembree, Meghan; Hodges, Nancy: Clothing the Virtual Self: An Exploration of the Purchase and Use of Virtual Apparel by Gamers. ITAA Proceedings, 2020

Jones, Stefanie: The Performance of Fat: The Spectre Outside the House of Desire. In: C. Pausé; J. Wykes; S. Murray (ed.): Queering Fat Embodiment. Farnham [Ashgate Publishing] 2014, pp. 31–47

Lebesco, Kathleen; Braziel, Jana Evans: Editor’s Introduction. In: Braziel, J.E.; LeBesco, K. (ed.): Bodies Out of Bounds: Fatness and Transgression. Berkeley [University of California Press] 2001, pp. 130–150

Lynch, Teresa; Tompkins, Jessica; Van Driel, Irene; Fritz, Niki: Sexy, Strong, and Secondary: A Content Analysis of Female Characters in Video Games across 31 Years. In: Journal of Communication, 66: 4, 2016

Ma, Jin Joo: Restructuring Situated Bodily Practices: Understanding the Relationship of Dress, Body, and Identity in Virtual Dressing Practice. In: Fashion Practice, 17(1), 2024, pp. 27–49

Mccomb, Sarah; Mills, Jennifer: The effect of physical appearance perfectionism and social comparison to thin-, slim-thick-, and fit-ideal Instagram imagery on young women’s body image. In: Body Image, Volume 40, 2022, pp. 165–175

Meadows, Mark Stephen: I, Avatar: The Culture and Consequences of Having a Second Life. 1st edition. New Riders, 2007

Park, Juyeon: The effect of virtual avatar experience on body image discrepancy, body satisfaction and weight regulation intention. In: Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 12(1), 2018

Park, Juyeon; Ogle, Jennifer Paff: How virtual avatar experience interplays with self-concepts: the use of anthropometric 3D body models in the visual stimulation process. In: Fashion and Textiles, 8, 28, 2021

Peters, Lauren Downing: Fashion Before Plus-Size: Bodies, Bias, and the Birth of an Industry. London [Bloomsbury Visual Arts] 2023

Puhakka, Anna M.: Exploring Fat Futures Studies: Venturing into preferable fat futures in the context of fat women’s physical activity. In: Excessive Bodies: A Journal of Artistic and Critical Fat Praxis and Worldmaking, 1:1, 2025, pp. 354–283

Puig, Krizia, And Schlauderaff Sav: Introduction to the Special Issue ‚Fat Matter(s): The Art-Science(s) of Future Body-Making. In: Fat Studies, 9:3, 2020, pp. 193–97

Roach-Higgins, Mary Ellen, & Eicher, Joanne B.: Dress and Identity. In: Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 10(4), 1992. pp. 1–8

Sardar, Ziauddin: The Namesake: Futures; futures studies; futurology; futuristic; foresight—What‘s in a name? In: Futures, 42: 3, 2010, pp. 177–184

Seely, Stephen D.: How do you dress a body without organs? affective fashion and nonhuman becoming. In: Women‘s Studies Quarterly, 41:1, (2013) pp. 247–265

Shin, Yeongyo And Lee, Selee: Issues of virtual fashion influencers’ reproduced bodies: a qualitative analysis based on body discourse. In: Fashion and Textiles, 10, 30, 2023

Smelik, Anneke: A posthuman turn in fashion. In: The Routledge Companion to Fashion Studies. 1st edn. London [Routledge] 2022, pp. 57–64

Volonté, Paolo: Fat Fashion: The Thin Ideal and the Segregation of Plus-Size Bodies. London [Bloomsbury Academic] 2021

Ward, Anna E.: Fat Bodies/Thin Critique: Animating and Absorbing Fat Embodiments. In: The Scholar and Feminist Online, Issue 11.3, 2013 https://sfonline.barnard.edu/fat-bodiesthin-critique-animating-and-absorbing-fat-embodiments/

Wykes, Jackie: Why Queering Fat Embodiment? In: C. Pausé, J. Wykes, S. Murray (ed.): Queering Fat Embodiment. Farnham [Ashgate Publishing] 2014, pp. 1–12

Yingling, Tosha: Fat Futurity. In: Feral Feminisms, Issue 5, 2016. https://feralfeminisms.com/fat-futurity/

Young, Leanne; Taylor, Catty: My Self, My Avatar, My Identity: Diversity and inclusivity within virtual worlds, 2021. Institute of Digital Fashion.

List of Figures

Fig. 1: DressX designs for the Covet Fashion game, 2025, featuring garments worn on physical and virtual bodies

Fig. 2: Screenshot of The Fabricant Instagram account dated February 13, 2020, featuring a virtual model of influencer Enama Siama

Biography

Gwyneth Holland is a lecturer in Fashion Marketing at the University of Westminster, specialising in consumer cultures and foresight. Over the past twenty years, Gwyneth has consulted for a range of leading brands, trends agencies and institutions, bringing a future lens to the fashion and lifestyle sectors. Her research focuses on futurity in fashion, and queer style cultures. Gwyneth is co-author of the book Fashion Trend Forecasting, which has become a core text for students around the world.

About this article

Copyright

This article is distributed under Creative Commons Atrribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0). You are free to share and redistribute the material in any medium or format. The licensor cannot revoke these freedoms as long as you follow the license terms. You must however give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. You may not apply legal terms or technological measures that legally restrict others from doing anything the license permits. More Information under https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.en.

Citation

Gwyneth Holland: Fashioning fat futures: virtual fashion and the body. In: IMAGE. Zeitschrift für interdisziplinäre Bildwissenschaft, Band 42, 8. Jg., (2)2025, S. 260-273

ISSN

1614-0885

DOI

10.1453/1614-0885-2-2025-16675

First published online

September/2025