By Petja Ivanova and Stefanie Mallon

Abstract

In her artistic practice, Petja Ivanova explores sensual and intimate casts of the human body, working at the intersection of material alchemy and digital speculation. Her ‘emo/exo-bodies’, textile sculptures made from bandages soaked in fermented chitosan, are both externalized emotional skins (exo) and embodied emotional states (emo). These porous exoskeletons function as somatic archives, holding the imprint of affective experience. Instrumentalizing the chitosan’s healing of the skin surface, Ivanova turns toward internal, emotional wounds, which are often neglected, feminized, or privatized, and treats them through what she frames as poetic futures and speculative ecologies on the spectrum of data healing.

In this interview with cultural anthropologist Stefanie Mallon, Ivanova reflects on the transfer of her emo/exo-bodies into digital space, the affective implications of this transition, and her search for a ‘somatic literacy’ attuned to the scars we are still in the process of making. Through 3D scanning, the textile forms are digitized, gaining a new kind of presence, which Ivanova calls ‘digital flesh’. In this process, the material reopens and becomes manipulable: stretched, reshaped, and written on. The wound is not closed but kept wide open, visible, evolving, and re-coded. This interview situates Ivanova’s practice within broader discussions of textile-based image practices in the digital age, and considers how her artistic work can act as a method of emotional processing, knowledge production, and structural critique.

In ihrer künstlerischen Praxis arbeitet Petja Ivanova mit intimen Abgüssen des menschlichen Körpers an der Schnittstelle zwischen Alchemie und digitaler Spekulation. Ihre „Emo/Exo-Körper“, textile Skulpturen aus mit fermentiertem Chitosan getränkten Verbandstoffen, sind sowohl externalisierte emotionale Hüllen (Exo) als auch verkörperte emotionale Zustände (Emo). Als poröse Exoskelette stellen sie somatische Archive dar, die den Abdruck affektiver Erfahrungen bewahren. Über die wundheilende Wirkung von Chitosan auf der Hautoberfläche wendet sich Ivanova auch inneren, emotionalen Wunden zu, die oft vernachlässigt, feminisiert oder privatisiert werden. Diese behandelt sie durch das, was sie als poetische Zukunftsvisionen und spekulative Ökologien im Spektrum der Datenheilung bezeichnet.

In diesem Interview mit der Kulturanthropologin Stefanie Mallon reflektiert Ivanova über den Transfer ihrer Emo/Exo-Körper in den digitalen Raum. Mithilfe von 3D-Scanning werden die textilen Skulpturen digitalisiert und so in ein Format überführt, das Ivanova als „digitales Fleisch“ bezeichnet. In diesem Prozess wird das Material auf alternative Weise zugänglich und manipulierbar: Es kann umgeformt und animiert werden. Dabei thematisiert Ivanova die affektiven Implikationen dieser Übertragung und ihre Suche nach einer „somatischen Kompetenz“. Denn auch in diesem Format werden die Wunden nicht geschlossen, sondern bleiben weit offen und sind sichtbar, entwickeln sich weiter und werden neu kodiert. Das Interview ordnet Ivanovas Praxis in eine breitere Diskussion über textilbasierte Bildpraktiken im digitalen Zeitalter ein und legt dar, wie ihre künstlerische Arbeit Emotionen, Wissensproduktion und Strukturkritik ins Zentrum stellt.

Introduction

By pressing bodies into bandages soaked in fermented chitosan, artist Petja Ivanova creates ‘emo/exo-bodies’. They are textile casts that are materially active and refer to emotional states: The chitosan’s wound-healing properties treat the body’s surface, while Ivanova‘s focus remains on emotional or psychic wounds beneath. In a gesture of translational intimacy, Ivanova 3D-scans these textile-bio constructs and transposes them into digital space. There, animated text flows across ‘digital flesh’, urging the viewers to ‘Keep their wounds wide open’. These wounds act as affective interfaces, channelling relational intensities across bodies, media, and temporalities. Thus, rather than being discrete objects, emo/exo-bodies behave as assemblages (cf. Deleuze/Guattari 1987; Bennett 2010), distributed and vibrating across the virtual and the material—and affect becomes a connective tissue.

Drawing on Luciana Parisi (2013), we consider the digital not just as a representational surface, but also as a computational logic that programs emotion and code into recursive loops of machinic sensing. For the artist, this implies that reality is not fixed, but a continuous state of transformation where materials, emotions, and meanings resist any closure. In line therewith, emo/exo-bodies do not distinguish between the organic and the synthetic, or between emotion and signal, but instead operate across the thresholds of affective computation and embodied becoming. Yet in addition to digital space, Ivanova’s emo/exo-bodies also manifest in the virtual realm, which we understand not only in terms of computer-generated environments, but also as a domain of potential, memory, and emotional excess.

In the following interview with cultural anthropologist and textile scientist Stefanie Mallon, Petja Ivanova describes the material and digital impressions she gained during her practical research. This reveals the hidden potentials of clothing, which remain relevant in an era of media images.

Interview

Stefanie Mallon: We are both textile enthusiasts. Let me start by asking how you value textiles as a material for your artistic work.

Petja Ivanova: Textiles have made a comeback as an artistic medium, and I am really glad that they are being recognized more as such. At the 2024 Venice Biennale, for instance, there were a lot more textile works than ever before. One conventional association people have with fabrics or textiles is that they are feminine materials (cf., for example, the Bauhaus), and have therefore not previously been considered competitive by those viewing art as a financial product. I sometimes shy away from using textiles in my own work. However, I came to recognize that I express myself most honestly through textiles. Working with textiles is something I feel tenderly drawn to. They make me feel connected to my ancestry and family. My grandmother, with whom I had a close relationship, used to make ten-metre-long carpets and aprons for folkloric dances all by herself. After she passed away, I took them all and saved them. I still cherish them, even though the moths are taking their toll. I believe textiles have a philosophical quality, not just because of what they represent, but also because of how they are made. Textile is a medium that carries time within it: It is made of repetition, patience, and embodied knowledge. The final product is never the only thing that matters; the process, movement and touch are also important. In that sense, working with textiles is a material form of thinking, a slow epistemology that resists speed, linearity, and disconnection. It holds technique, memory, and meaning together, quite literally, in every thread.

Stefanie Mallon: True, textiles are extremely diverse and their production methods can make them amazingly intricate and expressive. But in your work with emo/exo-bodies, you use very simple woven textiles. Could you explain how exactly you incorporate these into your practice?

Petja Ivanova: My emo/exo-bodies are based on two materials: One is gauze, which is used for dressing wounds. I have tested stretch gauze, but decided to use the plain old-school one, which is very loosely woven. It is fragile and not elastic at all, still can be made to fit perfectly around shapes when working with it sculpturally. The other material I am using is chitosan, which is a derivative of chitin, the second most abundant polysaccharide after cellulose. I find this fascinating, how something so plentifully available in our environments is used so little by us. It made me wonder why paper or cotton are so omnipresent in our cultures. Why do we not find ways to use this biomaterial? It is found in the exoskeletons of crustaceans and insects, creatures that are so important for our eco-systems, and who also have a repetitive habit to grow out of their shells. I became interested in this combination of chitin and gauze bandages, as it provides an easy and accessible way to make your own wound healing bandages.

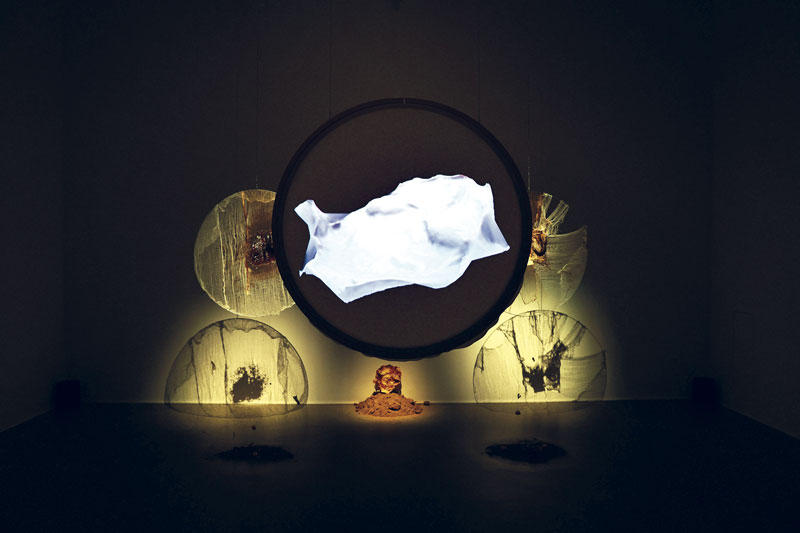

Fig.1: Chitosan cast, emo/exo-body, from Ivanova’s exhibition Soma of the Land at Folkwang Museum, Essen

To create the emo/exo-bodies, I first coat gauze bandages with vinegar, followed by a chitosan powder purchased from the pharmacy. Although there are various techniques to refine the process, such as freezing the material or applying dry ice on it, these methods are less relevant to the metaphorical and material semiotic potentials of this practice, so I no longer use them. What matters is how the material speaks; how it carries meaning through its texture, smell, and transformation. In this context, I keep thinking about Karen Barad’s concept of “agential realism” and how the apparatuses we use are not neutral observers, but active participants in the world’s becoming. They do not merely reflect reality, but help produce it through intra-actions that entangle matter and meaning. Scientific instruments and methods shape the phenomena they measure, just as discourse shapes meaning (Barad 2007). I see these wound-healing bandages as epistemological instruments that allow us to sense and construct alternative realities depending on how they are applied. Barad insists that matter and meaning are inseparable, and that materiality and discourse are intertwined. In this case, the bandage is not being used for its biochemical function, but rather as a textile tool—a means for thinking and feeling through materials and arriving at different kinds of knowledge.

I create a soft, malleable, and very sticky bio-fabric made of chitosan. It is wet to the touch and highly absorbent. If applied to a bleeding wound, it would stop the bleeding immediately. Chitosan carries a positive charge, which attracts the negatively charged membranes of red blood cells and platelets. This electrostatic interaction accelerates clot formation, and the material simultaneously absorbs blood, adhering to the skin to form a natural, gel-like seal. As it dries, the bandage transforms into a biopolymer—a bioplastic—which stiffens to retain the shape it had when wet, effectively holding the imprint of the wound, the contours of the skin, the pressure of touch. In this way, the material becomes a kind of somatic archive and a carrier of bodily memory, not only in its visible form, but also in its molecular responsiveness. However, even then, it remains responsive, slowly changing over time as it continues to absorb humidity from its surroundings. It never completely stops “intra-acting” (Barad 2007).

Stefanie Mallon: You mention the metaphorical and material semiotic potentials of your practice. Could you expand on that?

Petja Ivanova: The wound-healing bandage I work with is biochemically active: It physically stops bleeding. However, I have often felt that in present Western discourses, emotional wounds are more commonly discussed than literal, bleeding ones. This made me think: Could a material be created that attends to both? Could such a matter facilitate not only physical healing, but also the healing of emotional and psychological wounds—those that live under the skin and shape our sense of self? This led me to the concept of the ‘emo/exo-body’: a body turned inside out and made legible in its tenderness. This material is not just a metaphor; it has a real effect. It heals. I am not entirely comfortable with calling that symbolic. In the psychic sphere, we speak of heartbreak, wounds, pressure, and weight. Therefore, when I use a wound-healing material, I am not merely illustrating an emotion metaphorically, but I rather invoke an interconnected process of meaning and matter.

The bandage does not merely represent a wound; it is part of it, produces it alongside it, and may even help to transform it. Timothy Morton discusses the concept of the ‘strange stranger’, the notion that objects or beings can never be fully understood, but are constantly evading our grasp (Morton 2010). While Barad foregrounds entanglement and intra-action, and Morton insists on ontological withdrawal, both disrupt the centrality of the human as knower or agent. I think of this when working with materials such as chitosan: the bandage is not just a trace of feeling, it is a feeling, entangled with the body yet exceeding it, porous to its own ecology, and always slightly out of reach. It becomes an interface between the visible and the invisible, the biochemical and the emotional, and the internal and the external. In that sense, I do not see my work as metaphorical in the traditional sense. Rather, I see it as intra-active, to borrow Barad‘s term once again: Material and meaning emerge together through their entanglement.

Stefanie Mallon: So, in your work, meaning and material are entangled in the intra-active elements of chitosan, bandages, wounds and the body. How does fermentation come into play here?

Petja Ivanova: Fermentation is why I started making this material myself. There are actually two types of fermentation at play: I was drawn to fermentation as both a) a biochemical process and b) a feminist practice and technology.

Fermentation is a slow, non-linear process that often is invisible. Like the emotional and political labour carried out in feminist movements and healing, it requires care, patience, and trust in unseen transformations. It defies the industrial demand for speed and efficiency. It is collaborative, involving organisms, environments, and time. I see this as closely aligned with feminist ethics of interdependence and embodied knowledge. In my work, fermentation is a symbolic and material process of creating something new from what has been discarded or overlooked. This is comparable to how feminist practices often recover silenced voices, invisible labour, and ‘spoiled’ knowledge, giving them new meaning. In what she calls “fermenting feminism”, Lauren Fournier frames fermentation as both material and metaphor in and for feminist practices (Fournier 2020). Her curatorial and theoretical project explores how microbial transformation becomes a lens for trans-inclusive, intersectional feminist thought rooted in care, labor, and symbiotic ecologies. So, fermentation for me opens a portal of thinking of symbiotic relationships on far bigger scales than just in the jar.

There is also something remarkable about the way fermented materials refuse fixed states and continue to evolve. To me, this is a form of ‘soft power’. It is not about control, but about listening, adapting, and sensing. I therefore engage with fermentation not just as a method for producing biotextiles; but as a whole philosophy of transformation, knowledge sharing, and life unfolding in non-patriarchal narratives.

The fermentation of insect shells, specifically shrimp or insect exoskeletons, fascinates me in particular. While developing this material in 2018 and 2019, I came across a study showing that Lactobacillus bacteria can ferment chitin from these shells. Reading about it felt like rediscovering a long-lost, neglected or erased form of knowledge. Some scholars refer to this kind of loss as ‚epistemicide‘ (cf. Boaventura de Sousa Santos 2014), viz. the systematic destruction of entire knowledge systems, often resulting from colonial, religious, or scientific dominance. Yet I believe it does not only point to colonial erasures, but also to the historical effects of church-led suppression and the medical establishment’s monopolization of knowledge in European history. Furthermore, epistemicide is extremely relevant in fabric-making, given that textile heritages are prone to erasure. In my view, fermentation and fabric-making are parallel cultural practices: Both rely on embodied knowledge, sensory attunement, and intergenerational transmission. What struck me in the research on chitin fermentation was how contemporary bio-innovation seemed to ‘discover’ microbial processes that had long been part of vernacular or non-codified knowledge systems, especially those practiced outside institutional sciences. Rather than representing novel inventions, these findings often signal the delayed recognition or scientific legitimization of phenomena that have existed for centuries. The so-called ‘rediscovery’ of microbial fermentation, for example, parallels a wider turn toward pre-industrial, multispecies modes of knowing, especially in fields like regenerative medicine, biomaterials, or fermentation science, which are now revisiting techniques that were long dismissed or unrecorded in dominant scientific discourse. Thus, I consider fermentation a symbol for engaging with forms of knowledge that are known experientially or intuitively, but remain unacknowledged by dominant academic or scientific epistemologies. This is exactly what I intend with my work: to engage with minor forms of knowledge that are experiential, embodied, or intuitive.

We live in a time where emotional self-care, trauma healing, and personal transformation are highly visible and accessible through coaching, therapy, and wellness culture. But visibility does not necessarily equate to legitimacy or depth. Much of this knowledge is still considered ‘soft’, unscientific, or secondary, especially when it is practiced outside of its institutional frameworks. Knowledge about emotional wounds and the capacity to tend to them is rather privatized, feminized, or commodified, rather than treated as epistemologically valid or structurally supported. In my process, vinegar, as another fermented substance, acts as a catalyst. It affects the coloration and texture of the biopolymer. And vinegar stings, like emotional pain, but it also preserves our capacity for truth, integrity, and discernment, if integrated with awareness. Fermentation, in this context, becomes a tool in what I call a ‘socio-cultural technology’: a slow, alchemical transformation that mirrors the quiet but powerful labor of emotional processing.

Stefanie Mallon: You saturate the bandages in fermented chitosan and apply them to a physical body to highlight its vulnerable materiality. What does this vulnerable, material body represent in your art?

Petja Ivanova: The feminist literary theorist Hélène Cixous wrote that “when you write, you write out your body.” (Cixous 1976) By this, I believe she meant writing from within the body, as an embodied act, allowing language to emerge from desire, sensation, emotion, and physical memory. This idea has shaped how I understand the body, not simply as a biological entity, but as a narrative medium. Its materiality is a kind of story: experiences sedimented into flesh. Following theorists such as Lakoff and Johnson, I understand metaphor not just as a linguistic ornament, but as a fundamental structure of thought, rooted in bodily experience (Lakoff/Johnson 1980). When I speak of the body as a ‘container of time’ or a ‘site of connection’, I am not being figurative, but am articulating how embodied cognition frames our very sense of meaning. In this context, the term ‘emo’ is not just shorthand for ‘emotional’, but signals a cultural lineage in which emotional vulnerability is made visible, stylized, and shared. Emo/exo-bodies are thus not metaphors for something else; they are affective interfaces—where the interior world becomes communicable, perceptible, and material. They bring forth the unspeakable, the slow grief, the inherited ache.

Through my work, I resist the invisibilization of emotional labor, particularly the labor of tending to wounds caused by structural displacement or cultural assimilation. Each body carries these wounds differently. In my case, this includes a longing for zimnina, the deep, sensorial memory of fermented vegetables, a symbol of home, care, and survival in Eastern European winters. It also includes the psychic wound of being made to feel un-welcomed in the West: a subtle but persistent form of cultural marginalization experienced by those who migrate from ‘peripheral’ geographies. These, and many more unnamed affects, become emotional data points encoded in my bio-artifacts, perhaps as embodied inscriptions.

Stefanie Mallon: But with your artistic work, you are actually progressing from this physical body into the realm of emotions.

Petja Ivanova: Yes, exactly. I would not say that I frame my work directly through the body, but I do feel that the body, especially the emotional body, is profoundly porous. Particularly so by how affect moves through us, through screens, materials, even through time. It is not bound by the physical, but fluid and relational. Affect is what leaks out, what connects us to the world, and it is in this space that I work. Here, I am thinking with Sara Ahmed’s writing on how emotions circulate through and stick to bodies, materials, and histories (Ahmed 2004), and with Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick and Adam Frank’s understanding of shame as a relational, affective force that opens us to others, rather than enclosing us in pathology (Sedgwick/Frank 2003). Rather than a liability, I consider this porosity a modality of ‘soft power’, an epistemological stance that foregrounds receptivity, permeability, and affective entanglement as critical forms of resistance to the extractivist and securitized imperatives of dominant epistemologies.

My casts are like screenshots, not of the body in a literal sense, but of an emotional state captured in a fleeting moment. They are fragile because the moment is fragile. I am not interested in permanence, but in how something ephemeral, an inner wound, a sensation, can imprint itself into materials/the material, however temporarily. So yes, it is less about the body as a defined boundary, and more about how we are constantly being permeated: by time, memory, and feeling.

Stefanie Mallon: Let us step back from the physical body again to explore the inner wounds a bit more.

Petja Ivanova: Yes, I think, there is an emotional body that exists beyond the limits of our physical form, something that stretches across psychic, relational, and even ancestral terrain. These inner wounds live there. They are not always visible, but they shape how we move, relate, and sense. In a way, I see the inner wound as a kind of echo. It reverberates in the body but is not confined to it. It moves through material, sound, and gesture. And that is what I am often trying to trace in my work: these subtle, at times unspeakable imprints that we carry.

Stefanie Mallon: How are you connecting affect and emotion here?

Petja Ivanova: They are not the same, but they are deeply entangled. Affect, to me, is more pre-verbal—it is the felt sense that moves through us before it is named. Emotion is when we begin to make meaning of that affect, to narrate it, to attach it to experiences or stories (Massumi 2002). What feels crucial is cultivating a kind of ‘somatic literacy’, viz. the capacity to sense what is moving through us before it solidifies into language. In my work, I often try to stay with that raw affective terrain. It is like a shifting landscape, and sometimes the work is just to witness and materialize it, without rushing to resolve or explain it. Therefore, the important step is to understand that there is a landscape of affect which is moving through us, constituting us temporarily.

Aesthetics, in this context, can be understood as the sensory-affective interface where perception, sensation, and feeling become mediated through forms. In affect theory, aesthetics is often the space where affect emerges and circulates without being fully captured by emotion or rational meaning. It reminds me of something Agnès Varda said in The Beaches of Agnès (2008): “If we opened people up, we’d find landscapes.” It is a phrase I return to often, not just for its poetry, but because it gestures toward the interior as geographic, affective, and plural. It gives a shape to the idea that bodies are not bounded, but inhabited by memories, intensities, temporalities, and that art is a way to navigate those terrains.

Stefanie Mallon: Humans are not alone and singular in these emotional landscapes. Often, emotional wounds are inflicted by others or inflicted on others. So they connect them to other entities. How does this come into play when you appeal to ‘Keep your wounds wide open’. I would be interested to know more about what you mean by that.

Petja Ivanova: The phrase ‘Keep your wounds wide open’ is personal, but it also is a kind of methodology. Through working on and with emo/exo-bodies, I became more attuned to my emotional body, especially the subtle sensations that move through me. I live with anxiety, and there is a kind of quiet fear that sits in my body. Rather than trying to fix or suppress it, I started treating it as a portal.

At the same time, I started exploring a Bulgarian interpretive tradition of water spring dreams. These dreams are seen as messages or callings, often guiding people to sacred sites or water sources. They opened a path for me to explore place, memory, and embodied knowledge through more-than-rational means. That was when a kind of som(a)aesthetic landscaping emerged—a way of mapping emotional experience through the body and the land. I realized that my emotional wounds, particularly anxiety, were actually opening me to other ways of knowing. From that perspective, vulnerability is not weakness; it is knowledge. It is a different epistemological paradigm, where feeling and sensitivity can guide us towards an eco-connected or even cosmological consciousness, one in which body, land, and feeling are entangled ways of comprehending .

So, these fabrics I work with, they are not just healing materials. They are tools for attunement. They help access the body’s capacity to sense beyond itself, to connect to something larger. And in this sense, the open wound is both literal and metaphorical: It is the place where feeling enters, where we become permeable to others, to the environment, memory, and to time. And that is also where the irony comes in: If we only stay in the identity of ‘being wounded’, it can keep us stuck in loops, always returning to the same pain, the same narrative. But if we treat the wound as a passage rather than a definition, then it can become a site of connection, even transformation. So when I say ‘Keep your wounds wide open’, I mean: Let them breathe, let them guide you, but do not get trapped inside them.

Stefanie Mallon: So, you are talking about a particular consciousness, a connectedness with the living world …

Petja Ivanova: I use the term ‘the living world’ rather than ‘nature’ in order to emphasize relationality and reciprocity—a framing inspired by thinkers such as Robin Wall Kimmerer (2013), which intends to remind us that we are embedded in a world of kinship and exchange.

What fascinates me is that dreaming might be the way the body thinks. It is like an epistemology of the body, an embodied way of knowing that has not really been acknowledged in the history of Western science. This idea emerges from my own artistic research and somatic inquiry, where I observe how the body metabolizes experience not just through cognition, but through image, sensation, and symbolic processing, especially in dream states or meditations. In many Indigenous epistemologies, this connection between dreaming, body, and world has long been articulated: Dreams are not internal illusions, but relational transmissions, instructive and communal. I think my work is a small attempt to tune into that way of sensing and knowing.

Stefanie Mallon: So far, we have been talking about the analogue materiality of your art, but you are also a computer artist. What does the digital realm bring to your work?

Petja Ivanova: In 2009/2010, when I initially encountered micro-controllers as a student, it was a creativity explosion! It deeply fascinated me that I can just send something here, and then I can make a motor go there… just like that. It was like: Boom! All the things you could do, all the connections you can make, that were not there before. For instance, my very first project involved putting a light sensor into a pair of sunglasses. Through a little amplification device in the arms of the glasses, this would burn the skin behind my ears if I exceeded the time that my skin could naturally be exposed to the sun. These kinds of assemblages open up potentials for exemplifying connections that we usually would not make. I found that extremely fascinating.

However, the reason why I have moved away from computational art for a while, especially with fermentation, is that I found the applications and developments of technology just for technology‘s sake very unnecessary and boring. I did not want to take part in something which is just about showing how far the processor can go. I was more entertained, for example, by making metal fabric sensors for my underwear. They were programmed to change the weather pattern in a Virtual Reality app when the underwear got wet. So, these are things that are much more relevant than, for example, the introduction of the iPhone 15. Lately, I have become more interested in using accessible, low-threshold technologies, things like simple circuits sewn into underwear or open-source 3D scanning tools. There is something important about not overproducing the tech layer, but instead working with what is readily available, almost like digital folk practices. In this sense, I resonate with Olia Lialina’s (2010) reflections on early web aesthetics and the vernacular creativity of net users, where imperfection, hand-coding, and personal style created a kind of digital intimacy now largely lost in commercial platforms.

Fig. 2: Installation View Soma of the Land, hanging emo/exo-bodies, projection of animated exo-body scan

When I digitize the emo/exo-bodies, I use 3D scanning to give the fabric another kind of presence. It becomes ‘digital flesh’. The material reopens to become porous again. In its physical form, the fabric already carries a trace or an imprint of the emotional body. But when I move it into digital space, I can manipulate it: I can change its texture, sculpt it, and illuminate it. This opens another space of imagination, or even fantasy, where I can narrate or project meaning into the wound, which is not about realism, but about sensing. The digitized body lets me explore the emotional encoding I originally projected into the fabric in a new way. It becomes a vessel I can intra-act with, a site for writing, re-inscribing, and re-imagining.

Stefanie Mallon: And how do you work with and address it? What practices evolve within and from this transfer?

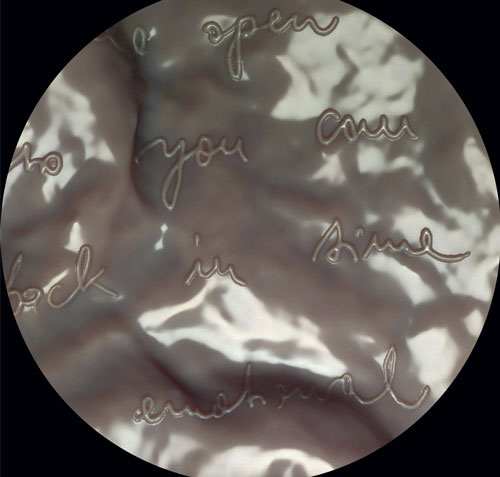

Petja Ivanova: I am obsessed with the idea of writing into this digital flesh, of using it as a surface for inscription, as if it were a scar in the making, a site of scarring and memory. For me, this is not just a visualization, but a process of embodiment, of renewal. The texture often resembles wounded skin, fresh and raw, but also alive and transforming.

Fig. 3: Animated text on 3d scanned digitally altered cast from Soma of the Land video work, 2024

In Soma of the Land, my solo exhibition at Museum Folkwang Essen in 2024, I explored this in more depth. I wanted the digital body to breathe, to absorb and emit language, to let words appear and disappear into the skin like flashes of memory. My 3D animation skills are still developing, so I collaborated with friends, wro wrezesinska and Carolina Ovando, to bring my pieces to life. But the core idea remained: This body, this wounded emotional body, could become a portal. A portal not only to feeling, but to ancestral or ecological consciousnesses, something that stretches beyond linear time and geography. So, in the digital, I do not just reproduce. I rewrite, re-sensitize, and invite the body to become a landscape of potential again.

Stefanie Mallon: Yes, you are definitely exploring a lot of new aspects of your work digitally, receiving productive input and inspiration from the transfer of material into digital spaces. Does this always add to the work, or is there also something that gets lost in such processes?

Petja Ivanova: Yes, there are definitely things that you cannot document. One of those are the relational aspects of actually making these casts. They plainly get lost in the process. For example, me and the people that I mould, we enter into close relationships when working together. There is this momentum when we talk and when we, through communication, touch, and the intimacy of our connection, have managed to address these wounds and to charge the invisible encoding of the material with personal meaning. You do not get this in digital spaces.

Another pertinent aspect that gets lost are the sensations, particularly the smells. The smell of vinegar is a little bit repellent. Such a confrontation with your own senses definitely is also lost in the digital, and at least until now, I have not heard of any way to integrate or replace it.

In her work “Succour”, the performance artist Kira O‘Reilly uses sticky tape to section the surface of her whole body into squares. In each of the squares she cuts her skin open to bleed. This is her way of drawing attention to the dichotomy between the datafication of the body versus its actual messiness. For her, wounds are the spaces where we become abject to ourselves, as I remember the artist explaining her performance. Materials outside the digital realm really carry a great amount of disgustingness!

Stefanie Mallon: You are firmly rooted in research. How do you go about researching these kinds of receptions or new practices? Could you provide an example?

Petja Ivanova: Yes, my practice is very research based. My friend Neema Githere (2023), a guerrilla theorist, is currently working on a theory focussed on data healing and re-indigenizing technology. I frame my practice as ‘poetic futures’ and ‘speculative ecologies’, which can be placed on the spectrum of data healing, as a kind of sprout. Me and my peers build alliances through the same kind of sensitization and sensitivities, and less through an overlapping of methods

Another project that I currently develop and that will likely take at least another year to realise, is an ‘emotional intimacy device’, something that, through resembling a Game Boy in form, evokes the nostalgia and technological heritage of early gaming devices. But rather than being purely about/concerned with entertainment, it shall confront the emotional body: to explore how the small screen, a familiar interface we often underestimate, can have somatic and psychological effects.

By this, I intend to reframe a technological object through the lens of affect. How do these devices shape our inner states? Can we design tools that support presence rather than dissociation? It is an experiment in what I might call ‘soft technology’, an interface that acknowledges how interaction always includes attunement. Roxanne Tiara (2020) speaks of ‘digital attunement’. As I understand it, this concept expresses that our nervous systems, our bodies, always relate, even adjust to the technology they are relating to/with. In this context, my emo/exo-bodies, and further works that I am planning, open up new forms of reception because they are not just looked at, but they are held, felt, and responded to. They ask the audience to sense how they somatically participate in human-technology intra-actions. They are not only about innovative art displays, but about creating situations where perception and sensation become tools for reflection, where the art object becomes a companion in a process of noticing, sensing, and potentially re-patterning one’s relation to technology, the self, and others.

Stefanie Mallon: What is your perspective on the innovative potentials involved in transferring materials into the digital? What novel practices evolve from this, and what do these imply for textiles?

Petja Ivanova: This digital attunement is not just a cognitive phenomenon; it is somatic. It teases the body. It is a form of sensing, and perhaps even re-sensitizing. I see attunement as a practice—a form of embodied literacy. Tiara Roxanne’s work reminds us that the digital is never disembodied. It is always entangled with histories of land, flesh, displacement, and perception. When we transfer affective material into digital space—whether through scanned textiles or animated forms—we are not losing the body. We are reconfiguring it, re-locating its perceptual and expressive capacities into a new plane of mediation. This is where new practices evolve, not only artistic but also epistemological ones. Thinking is, of course, a practice. Feeling and sensing are materialities that move through bodies, time, and technologies. Affect travels or sticks, leaps, echoes. Media theorists like Anna Munster or Laura Marks have written beautifully about how digital images are not just visual, but rather touch us, carry intensities. There is a tactile, haptic dimension to digital experience that is often overlooked. So, when I digitize emo/exo-bodies, I am not just documenting something. I rather extend its perceptual field, allowing a kind of feedback loop where the emotional imprint can be re-read, re-written, or even re-felt by others. This is why I say that sculpting with digital textures is not about realism, but about accessing that traveling materiality of feeling. It is about creating space for a different kind of encounter, which is intimate, imaginative, and affectively charged.

All this has particular implications for textiles. Fabric is already a recording device, a medium that remembers folds, frictions, pressures, and proximities. When we scan or digitize textile-based works, we are not neutralizing that memory, but transposing it. The weave, the stretch, the irregularities, they carry affective residues. In digital space, these details can be amplified, manipulated, reanimated. I think this opens up entirely new vocabularies for textile practices, where material memory becomes mutable, where softness can glitch, and where wounds can be re-rendered as light, shadow, or movement. It allows us to imagine textiles not just as surfaces, but as dynamic carriers of emotion and knowledge across mediums. The digital becomes a loom in itself, that weaves together sensation, history, and speculation. In this sense, the transfer into digital space does not flatten textile practices, but deepens their reach. It enables fabrics to speak in frequencies we did not know they could.

Stefanie Mallon: Thank you! I am really looking forward to finding out more about your new work soon.

Petja Ivanova: Thank you so much for your interest in what I am doing, and for your intriguing questions!

Images

Image 1: chitosan cast, emo/exo-body, from exhibition Soma of the Land (Ivanova)

Image 2: Installation View Soma of the Land, hanging emo/exo-bodies, Projection of animated exo-body scan (Ivanova)

Image 3: Animated text on 3d scanned digitally altered cast from Soma of the Land video work, 2024 (Ivanova, Wrezesinska, Ovando)

Literature

Ahmed, Sara: The Cultural Politics of Emotion. Edinburgh [Edinburgh University Press] 2004

Barad, Karen: Meeting the universe halfway: Quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Durham, North Carolina [Duke University Press] 2007

Bennett, Janet: Vibrant matter: A political ecology of things. Durham, North Carolina [Duke University Press] 2010

Cixous, Hélène.: The Laugh of the Medusa (K. Cohen & P. Cohen, Trans.). In: Signs 1(4), 1976, pp. 875–893. https://doi.org/10.1086/493306

Deleuze, Gilles; Guattari, Felix: A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia. (B. Massumi, Trans.). Minneapolis, Minnesota [University of Minnesota Press] 1987

Fournier, Lauren: Fermenting Feminism as Methodology and Metaphor: Approaching Transnational Feminist Practices through Microbial Transformation. In: Environmental Humanities 12 (1), 2020, pp. 88–112. https://doi.org/10.1215/22011919-8142220

Githere, Neema: Data Healing Workbook. Stanford University’s Digital Civil Society Lab. 2023. https://www.findingneema.online/data-healing/the-data-healing-workbook

Lakoff, G.; Johnson, M.: Metaphors we live by. Chicago, Illinois [University of Chicago Press] 1980

Lialina, O.: A Vernacular Web. Art. Teleportacia, 2005. https://art.teleportacia.org/observation/vernacular/

Massumi, Brian: Parables for the Virtual: Movement, Affect, Sensation. Durham, North Carolina [Duke University Press] 2002

Morton, Timothy: Hyperobjects: Philosophy and ecology after the end of the world. Minneapolis, Minnesota [University of Minnesota Press] 2013

Morton, Timothy: The ecological thought. Cambridge, Massachusetts [Harvard University Press] 2010

Rao, Mukku Shrinivas; Willem F. Stevens: Chitin production by Lactobacillus fermentation of shrimp biowaste in a drum reactor and its chemical conversion to chitosan. In: Journal of Chemical Technology and Biotechnology 80(9), 2005, pp. 1080–1087. https://doi.org/10.1002/jctb.1286

Santos, Boaventura de Sousa: Epistemologies of the South: Justice Against Epistemicide. New York [Routledge] 2014

Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky; Adam Frank: „Shame in the Cybernetic Fold: Reading Silvan Tomkins.“ In: Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity, pp. 93–122. Durham, North Carolina [Duke University Press] 2003

Roxane, Tiara: Digital Attunement (an Introduction). Queer.Archive.Work 2020

Varda, Agnès: The Beaches of Agnès. Les Films du Losange [France] 2008

Biographies

Petja Ivanova is an artist, researcher, and performer from Bulgaria, who is working via her Studio for Poetic Futures & Speculative Ecologies. Her practice oscillates between somatic intelligence, planetary consciousness, and technological critique, cultivating new forms of knowing that are rooted in vulnerability, the spirit of the living world, and embodied connections to the planet.

Stefanie Mallon is a cultural anthropologist and textile scientist at the University of Göttingen, Germany, with a research focus on Critical Fashion and Textiles. Recent publications include the anthology Decentering Fashion on the Silk Roads, an article on Digital fashion and the future of fashion, and an empirical study on fungus as an alternative to leather. She works for the Responsible Fashion Series, which brings together fashion activists from academia and practice at its international events, aiming to develop actionable ideas for a responsible fashion system.

About this article

Copyright

This article is distributed under Creative Commons Atrribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0). You are free to share and redistribute the material in any medium or format. The licensor cannot revoke these freedoms as long as you follow the license terms. You must however give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. You may not apply legal terms or technological measures that legally restrict others from doing anything the license permits. More Information under https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.en.

Citation

Petja Ivanova, Stefanie Mallon: Emo/exo-bodies in analogue and digital spaces: towards a somatic literacy of digital flesh. In: IMAGE. Zeitschrift für interdisziplinäre Bildwissenschaft, Band 42, 8. Jg., (2)2025, S. 242-259

ISSN

1614-0885

DOI

10.1453/1614-0885-2-2025-16673

First published online

September/2025